ලංකාවට සමාජජාල ගැන විචාරයක් නැහැ. මෙන්න එහෙම එකක්.

social media is the new (digital) version of the Other, which we are all desperately wanting to exist, to recognise us, to save us. In this sense, social media is ‘the social’, is ‘society’- Prof Nalaka

It must also be said that “the social” could only become technical, and become so successful, after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, when state communism no longer posed a (military) threat to free-market capitalism.

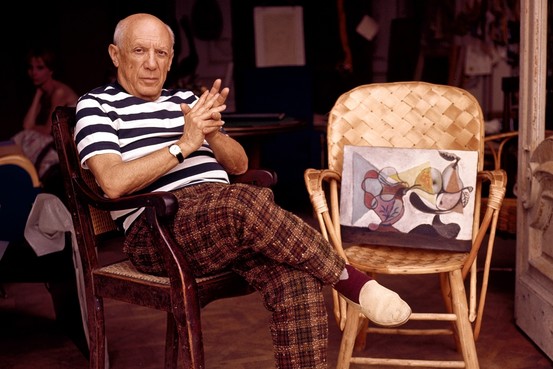

if we want to answer the question of what the “social” in today’s “social media” really means, a starting point could be the notion of the disappearance of the social as described by Jean Baudrillard, the French sociologist who theorized the changing role of the subject as consumer. According to Baudrillard, at some point the social lost its historical role and imploded into the media. If the social is no longer the once dangerous mix of politicized proletarians, of the frustrated psychotics , unemployed, and dirty clochards, University Don’s that hang out on the streets waiting for the next opportunity to revolt under whatever banner, then how do social elements manifest themselves in the digital networked age?

The container concept “social media,” describing a fuzzy collection of websites like Facebook, Digg, YouTube, Twitter, and Wikipedia, is not a nostalgic project aimed at reviving the once dangerous potential of “the social,” like an angry mob that demands the end of economic inequality. Instead, the social—to remain inside Baudrillard’s vocabulary—is reanimated as a simulacrum of its own ability to create meaningful and lasting social relations. Roaming around in virtual global networks, we believe that we are less and less committed to our roles in traditional community formations such as the family, church, and neighborhood. Historical subjects, once defined as citizens or members of a class possessing certain rights, have been transformed into subjects with agency, dynamic actors called “users,” customers who complain, and “prosumers.” The social is no longer a reference to society—an insight that troubles us theorists and critics who use empirical research to prove that people, despite all their outward behavior, remain firmly embedded in their traditional, local structures.

The social no longer manifests itself primarily as a class, movement, or mob. Neither does it institutionalize itself anymore, as happened during the postwar decades of the welfare state. And even the postmodern phase of disintegration and decay seems over. Nowadays, the social manifests itself as a network. Networked practices emerge outside the walls of twentieth-century institutions, leading to a “corrosion of conformity.” The network is the actual shape of the social. What counts—for instance, in politics and business—are the “social facts” as they present themselves through network analysis and its corresponding data visualizations. The institutional part of life is another matter, a realm that quickly falls behind, becoming a parallel universe. It is tempting to remain positive and portray a synthesis, further down the road, between the formalized power structures inside institutions and the growing influence of informal networks. But there is little evidence of this Third Way approach coming to pass. The PR-driven belief that social media will, one day, be integrated is nothing more than New Age optimism in a time of growing tensions over scarce resources. The social, which used to be the glue for repairing historical damage, can quickly turn into unstable, explosive material. A total ban is nearly impossible, even in authoritarian countries. Ignoring social media as background noise also backfires. This is why institutions, from hospitals to universities, hire swarms of temporary consultants to manage social media for them.

Social media fulfill the promise of communication as an exchange; instead of forbidding responses, they demand replies. Similar to an early writing of Baudrillard’s, social media can be understood as “reciprocal spaces of speech and response” that lure users to say something, anything.2 Later, Baudrillard changed his position and no longer believed in the emancipatory aspect of talking back to the media. Restoring the symbolic exchange wasn’t enough—and this feature is precisely what social media offer their users as an emancipatory gesture. For the late Baudrillard, what counted was the superior position of the silent majority.

Social media as we know them right now are not discursive machines. The internet in general might be, in theory, but the current social media architectures do not facilitate extensive exchanges. There is a historical reason for this. Social media grew out of a specific part of web culture of the blogs, in the early 2000s, after the baroque and excessive dotcom period of e-commerce had fallen to pieces. Social media picked up on the ‘updating’ part of blog culture, and stripped off the content bit. There is a reason why Twitter is limited to 140 characters. There was no technological limitation (not enough bandwidth, computing power, interface etc.). The same can be said of Facebook’s aversion to discussion and debate. For a good decade already Facebook has been repressing the user’s need for community tools. There is no value in it for them. People need to like and share, say something fast and move on.

The arts do not need quick responses but thorough reflection and then debate about the positions people have formulated. Criticism presumes careful observation. This is then filtered through a rich vocabulary which every discipline has developed over the past decades and even centuries. Believe it or not, this even exists in the case of the internet. The fact that curators and e-flux discourse managers in particular strategically position themselves outside of this (with publication titles such as ‘The Internet Does Not Exist’) tells us more about the awkward position the contemporary arts scene has maneuvered itself into, now that everyone is online 24/7, is walking around with smart phones everywhere (incl. museums) and the relevant visual culture production (and related conversations) has effectively migrated to platforms such as YouTube, Tumblr and Instagram.

— Art involves a great deal of interpretation, so how does the gallery’s presence on Facebook or other social platforms enable visitors to voice their own interpretations about art and what does this add to an understanding of the work? How is artistic interpretation benefited through comment culture?

—- It doesn’t. Art galleries cannot compensate for the current poverty of the dominant social media platforms that were neither built to expand on details and provide insight nor to spark debate beyond likes and short remarks. Social media platforms as we know them are deeply commercial ‘machines of loving grace’ that aim to provide other machines with valuable data (clicks on ads etc.). The arts are not operating outside of the ‘clickbaiting’ mechanism. The museum sector is completely part of the advertisement ecology in which Google and Facebook play a dominant role. I cannot stress enough the important work that Douglas Rushkoff is doing in this context. Please all look his 2014 PBS documentary ‘Generation Like’. Keep in mind that contemporary arts does not operate outside of the branding reality, even though we advocate a critical stand or even deal with political art works. ‘Terms and Conditions May Apply’ from 2013 is also still relevant, as is the work of Andrew Keen and Evgene Morozov, and many others. The systematic denial among arts officials of the social media hegemony is a painful self-delusion. We’re all subjected to this new political economy of the platforms. It’s never too late to catch up these issues as it is only getting more important. The idea of social media as hype that will fade away next season is short-sided and counter-productive. This topic needs our urgent attention.

–Does the ‘openness’ to external voices exemplify democracy in action or just the rhetoric of tech companies when taking place on social media?

—: There is no ‘openness’ whatsoever. Social media were not designed to foster debate. All they do is ‘monitor’ short exchanges and impressions. The platforms are used as measurement tools in marketing campaigns. The related ad firms in the background measure likes and retweets and clicks and sell these data profiles to third parties. It does not matter what people say on Facebook or Twitter, and the actual work on social media has been delegated to interns inside PR departments. There are large offices that do the ‘twittering’ for celebrities and CEOs and give constant feedback about the latest ups and downs. If we want to oppose this logic, we need to start building hybrid offline and online networks from scratch. These days that’s very easy to do and there is a whole array of online tools to do this. Every subculture has its own preferences. In the end it is not decided by what software you’ve chosen but whether you’ve been able to cultivate real online conversations that have multiple consequences in both the real and the virtual world. What counts is the density and richness of the real existing online culture. Users immediately recognize it if the dialogue is fake.

Fuck me harder darling……Fuck me ….. Fuck me…