Will the post EU referendum chaos give the Left space to redefine itself?

Late in his life, Freud asked the famous question “Was will das Weib?”, “What does a woman want?”, admitting his confusion when faced with the enigma of the feminine sexuality. A similar perplexity arouses today, apropos the Brexit referendum—what does Europe want?

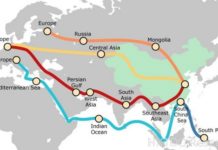

The true stakes of this referendum become clear if we locate it into its larger historical context. In Western and Eastern Europe, there are signs of a long-term re-arrangement of the politica. Until recently, the political space was dominated by two main parties which addressed the entire electoral body, a Right-of-centre party (Christian-Democrat, liberal-conservative, populist) and a Left-of-centre party (socialist, social-democratic), with smaller parties addressing a narrow electorate (ecologists, neo-Fascists). Now, a singular party is emerging which stands for global capitalism as such, usually with relative tolerance towards issues such as abortion, gay rights, religious and ethnic minorities; opposing this party is a stronger anti-immigrant populist party which, on its fringes, is accompanied by directly racist neo-Fascist groups.

Poland is a prime example—after the disappearance of the former Communists, the main parties are the “anti-ideological” centrist liberal party of the former prime-minister Donald Tusk (now President of the European Council) and the conservative Christian party of Kaczynski brothers (identical twins one of whom served as Poland’s president from 2005-2010 and the other as its prime minister 2006-2007). The stakes of Radical Center today are: which of the two main parties, conservatives or liberals, will succeed in presenting itself as embodying the post-ideological non-politics against the other party dismissed as “still caught in old ideological specters”? In the early 90s, conservatives were better at it; later, it was liberal Leftists who seemed to be gaining the upper hand, and now, it’s again the conservatives.

The anti-immigrant populism brings passion back into politics, it speaks in the terms of antagonisms, of Us against Them, and one of the signs of the confusion of what remains of the Left is the idea that it should take this passionate approach from the Right: “If the leader of France’s National Front Marine le Pen can do it, why we should also not do it?” So should the Left then return to advocating for strong nation-states and mobilize national passions—a ridiculous struggle, lost in advance.

Europe is caught into a vicious cycle, oscillating between the Brussels technocracy unable to drag it out of inertia, and the popular rage against this inertia, a rage appropriated by new more radical Leftist movements but primarily by Rightist populism. The Brexit referendum moved along the lines of this new opposition, which is why there was something terribly wrong with it. Look at the strange bedfellows that found themselves together in the Brexit camp: right-wing “patriots,” populist nationalists fuelled by the fear of immigrants, mixed with desperate working class rage—is such a mixture of patriotic racism with the rage of “ordinary people” not the ideal ground for a new form of Fascism?

The intensity of the emotional investment into the referendum should not deceive us, the choice offered obfuscated the true questions: how to fight trade “agreements” like the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership ( TTIP) which present a real threat to popular sovereignty and how to confront ecological catastrophes and economic imbalances which breed new poverty and migrations. The choice of Brexit means a serious setback for these true struggles—it’s enough to bear in mind what an important argument for Brexit the “refugee threat” was. The Brexit referendum is the ultimate proof that ideology (in the good old Marxist sense of “false consciousness”) is alive and well in our societies.

When Stalin was asked in the late 1920s which political variation is worse, the Right one or the Leftist one, he snapped back: “They are both worse!” Was it not the same with the choice British voters were confronting? Remain was “worse” since it meant persisting in the inertia that keeps Europe mired down. Exit was “worse” since it made changing nothing look desirable.

In the days before the referendum, there was a pseudo-profound thought circulating in our media: “whatever the result, EU will never be the same, it will be irreparably damaged.” But the opposite is true: nothing really changed, except that the inertia of Europe became impossible to ignore. Europe will again waste time in long negotiations among EU members that will continue to make any large-scale political project unfeasible. This is what those who oppose Brexit didn’t see—shocked, they now complain about the “irrationality” of the Brexit voters, ignoring the desperate need for change that the vote made palpable.

The confusion that underlies the Brexit referendum is not limited to Europe—it is part of a much larger process of the crisis of “manufacturing democratic consent” in our societies, of the growing gap between political institutions and popular rage, the rage which gave birth to Trump as well as to Sanders in the US. Signs of chaos are everywhere—the recent debate on gun control in the US Congress descended into a sit-in protest by the Democrats—is it time to despair?

Recall Mao Ze Dong’s old motto: “Everything under heaven is in utter chaos; the situation is excellent.” A crisis is to be taken seriously, without illusions, but also as a chance to be fully exploited. Although crises are painful and dangerous, they are the terrain on which battles have to be waged and won. Is there not a struggle also in heaven, is the heaven also not divided—and does the ongoing confusion not offer a unique chance to react to the need for a radical change in a more appropriate way, with a project that will break the vicious cycle of EU technocracy and nationalist populism? The true division of our heaven is not between anemic technocracy and nationalist passions, but between their vicious cycle and a new pan-European project which will addresses the true challenges that humanity confronts today.

Now that, in the echo of the Brexit victory, calls for other exits from EU are multiplying all around Europe, the situation calls for such a project—who will grab the chance? Unfortunately, not the existing Left which is well-known for its breathtaking ability to never miss a chance to miss a chance.