In roughly a decade, Africa has gone from being labeled “the hopeless continent” to enjoying an unprecedented boom. In a three-part series, SPIEGEL explores this transformation — its drivers, winners and losers — and asks if it can last.

The magazine cover bore a completely black background. In the middle, an outline the shape of Africa framed a fierce-looking fighter toting a rocket-propelled grenade launcher. Above the picture was the title, “The hopeless continent.”

This cover of British magazine the Economist, the world’s most influential newsmagazine for business and financial topics, appeared in May 2000. The issue featured a deeply pessimistic report that tore Africa to pieces, presenting it as a lost continent, eternally plagued by tribal wars, famine and mass poverty.

But since the turn of the millennium, the world has a different take on Africa thanks to an economic boom that refuses to fit into the usual distorted picture. The same voices that once proclaimed the continent dead are now predicting a rebirth for Africa, the awakened giant with nearly incalculable natural resources (around 40 percent of the world’s raw materials and 60 percent of its uncultivated arable land), fast-growing markets and a young, highly motivated population.

Indeed, while he was still president of Nigeria, Olusegun Obasanjo proclaimed that the 21st century would be “the century of Africa.”

A Second ‘Scramble for Africa’?

Here are the facts behind the fiction: No other continent has developed as rapidly in the last decade as Africa, where real economic growth was between 5 and 10 percent annually. In oil-rich countries, such as Angola, it was a possibly record-breaking 22.6 percent in 2007.

A World Bank study shows that 17 of the 50 national economies currently displaying the greatest economic progress are in Africa. The gross domestic product of the continent as a whole — over $1.7 trillion (€1.3 trillion) — is nearly equal to that of Russia.

Africa is showing its true potential and offers “myriad opportunities” that investors can no longer afford to ignore, says the German consultancy firm Roland Berger.

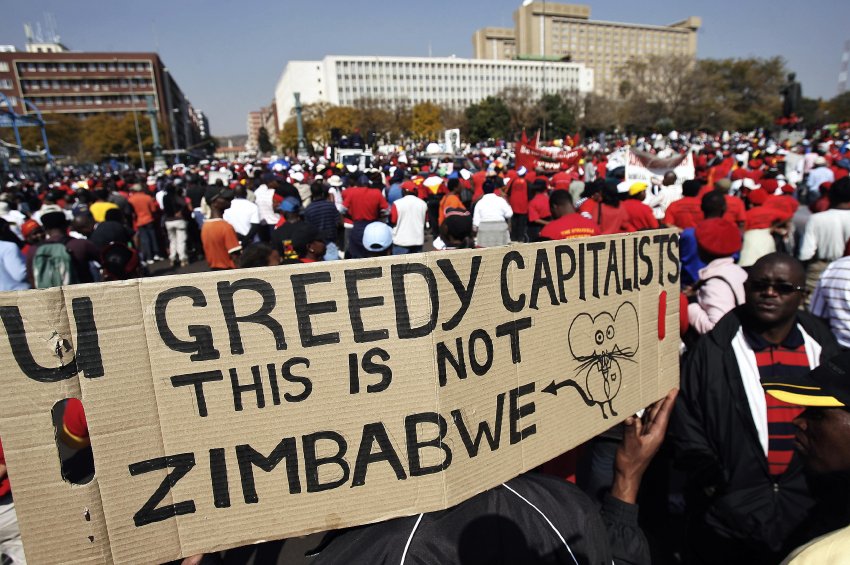

With not much going on in Europe and the United States at the moment as a result of the financial crisis and ensuing austerity policies, investors and speculators are discovering the African continent, where investment funds that speculate in natural resources, food and agricultural land promise fabulous yields.

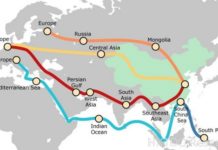

This development has historians talking about a potential second “scramble for Africa,” comparable to the period in the late 19th century when European colonial powers carved up the continent among themselves and plundered its resources. Now, in the age of globally unleashed capitalism, new competitors have entered the race, including India, Brazil and smaller emerging markets, such as Turkey. First and foremost in this modern-day scramble, though, is China.

Fresh Beginnings and Leapfrogged Eras

The world’s largest economy has overtaken the West to become Africa’s most important trade partner. The volume of Sino-African trade amounted to nearly $200 billion last year. Driven by an insatiable hunger for raw materials and mass markets, China is conquering the continent with such determination that African intellectuals warn of a new form of Chinese colonialism. Still, most Africans see this new global player’s involvement as an opportunity to break free of poverty.

Africa’s boom can be seen in many indicators: the volume of cars (and accompanying traffic jams) on the streets of its major cities, the glittering shopping malls and the major infrastructure projects. Highways, rail lines, airports, dams, power plants, pipelines and factories are all being built, and megacities such as Lagos, Nairobi, Addis Ababa are seeing the emergence of industrial parks and special economic zones.

It’s the start of a period of new growth and fresh beginnings, and many Africans seem more confident now than they have at any other time since the end of the colonial era, in the early 1960s. Economists attribute this to three main factors: political stability, economic reforms and a push toward technological innovation that has gripped the entire continent.

Many countries have become better governed, and Africa as a whole is more peaceful and democratic than it once was. When the Cold War ended, just three out of 53 African nations had halfway functional democracies. Today, that figure is 25 out of 54. Aside from chronic conflict zones — such as those in Congo, Sudan and Somalia — the number of civil wars and military coups has decreased, as has the excessive use of violence.

At the same time, a revolution is taking place in the information and communications sector, as Africa connects itself to the world via modern data highways. Nowhere is the spread of the Internet as all-encompassing as it is between Cairo and Cape Town, and nowhere is mobile-phone use increasing as explosively. There are now 650 million African mobile-phone users — more than in North America.

In Kenya, young local IT experts are doing globally pioneering work in developing innovative mobile-phone applications. Development experts call this “leapfrogging”: As Africa catches up on modernization, it is able to skip the industrial age completely and jump straight to the digital future. And free access to information in turn stimulates economic activity, strengthens civil society and brings about societal change, especially in major cities. In this way, the young people and women of Africa are emancipating themselves.

Driving this progress is a new middle class, which the African Development Bank estimates encompasses over 310 million people — roughly equivalent to the population of the US.

‘Lion’ Nations

Those who have made it into this African middle class don’t fit the cliché of the helpless, destitute African. These are self-confident citizens who have jobs, buy apartments and invest in their children’s education, just as members of the middle class do around the world.

“The lions are on the move” is the new motto of the African elite, with the phrase being a play on the term “Asian tiger.” After decades of decline, African nations are hoping to benefit from the same demographic dividend that made it possible for countries such as South Korea and Taiwan to make a leap of progress. By 2050, at least 2 billion people will live in Africa, accounting for one quarter of the world’s labor force.

Skeptics, though, pose the question of whether Africa’s current economic miracle might be nothing but a flash in the pan, fueled primarily by high raw-material prices and improving life for only a thin layer of the upper class. In resource-rich countries, such as Gabon and Angola, many people experience those resources not as a blessing, but a curse. While those in power grow rich unchecked, everyone else remains just as poor as ever.

Millions of Africans continue to go to bed hungry. Millions suffer from disease and epidemics. Millions of children attend abysmal schools.

Nevertheless, the economic growth is bearing its first fruits. In many places, living conditions have visibly improved. Child mortality, illiteracy rates and AIDS infection rates are declining, and life expectancy has increased by 10 percent.

Even those with a pessimistic view of Africa are looking on in astonishment as the continent once considered an ailing giant gradually picks itself up off the ground. In fact, Africa’s economic successes of the last decade have most likely had more of a positive impact on it than all the development aid it received over the last half-century.

The ‘Continent of the Future’?

Is Africa the continent of the future? Economists such as Robert Kappel and Birte Pfeiffer at the German Institute of Global and Area Studies (GIGA), in Hamburg, praise the progress of individual countries. But they also caution against getting carried away by euphoria. The majority of the 48 sub-Saharan nations still fall at the very bottom of the list when it comes to global prosperity, they point out, with few truly having managed to catch up to the rest of the world. Effusive comparisons with the “Asian tiger” nations, they say, are “not very apt.”

There’s a danger that homegrown problems — government failure, mismanagement, nepotism, endemic corruption and capital flight — could quickly undo the continent’s recent accomplishments. If these current changes are to be sustainable, Africans must finally liberate themselves from the kleptocrats who rule them.

Courtesy- SPIEGEL