It is difficult to do justice to the mood of despair that has been haunting the corridors of the Commonwealth Secretariat’s headquarters in Marlborough House in recent months. The decision to hold the 2013 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Sri Lanka has led, with grim inevitability, to a public relations disaster.

The choice of location was first made in 2009 at the end of a brutal civil war in which government forces had, at best, acted with a callous disregard for the safety of Tamil civilians. Indeed, the brief intervening period has witnessed both credible allegations that war crimes were committed and growing signs of authoritarianism on the part of the regime of Mahinda Rajapaksa.

The announcement at the weekend that Manmohan Singh, prime minister of India, would be following the lead of Canadian premier, Stephen Harper, and boycotting the summit can only have added to the sense of gloom. Of course, CHOGMs in earlier decades were sometimes turbulent affairs. But that was because there were genuinely contentious issues at stake. The current controversy is an entirely self-inflicted wound which makes a mockery of the Commonwealth’s supposed commitment to human rights. In private at least, this is now being acknowledged by senior figures in the secretariat.

What is it good for?

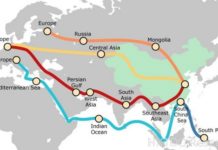

For many people, the Commonwealth has long been of such little relevance that the causes of its present difficulties hardly matter. Hopes in Whitehall that it might serve to bolster Britain’s global power in the post-war era had largely been abandoned by the 1960s. Thereafter, it was taken up by the new rulers of Britain’s former colonies as a useful forum within which to press for an end to white domination in southern Africa. Once that objective appeared to have been achieved in the early 1990s, it again faced an identity crisis.

An attempt to reinvent the organisation as a champion of democracy, good governance, human rights and development has failed to give it the sense of purpose and momentum offered by the crusade against apartheid. Commonwealth heads of government regularly put their names to seemingly exhaustive statements of good intentions. Yet the organisation lacks the influence, cohesion or capacity to translate these warm words into action.

The current government has been keen to proclaim its support of the organisation, partly, one suspects, because this plays well with Tory Euro-sceptics for whom the idea that the Commonwealth could replace the EU as Britain’s principal trading partner remains a potent fantasy. Yet the Cameron administration seems to have no more of a clue than its predecessors did about how to make the most of the organisation as a diplomatic resource.

An ex-parrot

A symptom of this malaise is the increasing prominence given to the Queen’s role as head of the Commonwealth. Whereas in the 1970s Commonwealth insiders tended to see the headship as a faintly embarrassing throwback to imperialism, they now cling to it as the only consistently newsworthy aspect of their organisation. A former prime minister of New Zealand once famously described the Queen as “the bit of glue that somehow manages to hold the whole thing together”. Increasingly, however, the Commonwealth resembles a dead parrot which relies on that glue to keep it upright on its perch.

Under the circumstances, the task facing any Commonwealth secretary-general would be a thankless one. Nevertheless, the performance of the current incumbent has been notably lacklustre. Kamalesh Sharma is an extremely nice man and a distinguished diplomat. Yet he has provided his organisation with neither a distinctive public voice nor a cogent and innovative vision for the future.

Marlborough House has largely abandoned any attempt to defend the decision to hold the CHOGM in Sri Lanka. Instead, it merely shuffles off responsibility onto the heads of government who agreed the venue in the first place. Yet such decisions are arrived at by a “consensus” among more than 50 member states. As guardian of the reputation and values of the Commonwealth, the secretary-general has a duty to guide that consensus and warn against decisions that would tarnish the image of the organisation. In the face of relentless lobbying from the Sri Lankan government, Sharma conspicuously failed in his duty.

The only winner

By contrast, this has been a diplomatic triumph for the one member state that seems to have had a clear strategy for putting the Commonwealth to work in its interests. British ministers regularly repeat the cliché that the Commonwealth is a form of “soft power”. The question has always been “soft power for whom?” The answer is now clear: soft power for Sri Lanka.

The Sri Lankan government has long craved the international respectability accorded to the host of a CHOGM. Despite mounting criticisms of its human rights record, it appears to now be achieving this goal as Rajapaksa begins his two-year tenure as chair-in-office of the Commonwealth.

There is certainly a lesson here for countries that want to pursue “soft power” through the Commonwealth, although one that the UK would find it difficult to emulate, precisely because it would attract accusations of “neo-colonialism”.

For many of those who have supported it loyally in the past, however, the prospect of the Commonwealth becoming a soft power vehicle for the Rajapaksa regime is likely to be more than they can stomach. Instead of merely spouting platitudes about the value of the Commonwealth, the Cameron government should follow the example of the Canadian government and take a long, hard look at this troubled organisation. It may well be that, at least from a UK perspective, the Commonwealth as currently configured has reached the end of its useful life.