And at the ninth hour, Jesus cried out with a loud voice, “Eloi Eloi lama sabachthani?” which means, “My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me?” It is the only saying that appears in more than one Gospel, and is a quote from Psalm 22:2. This saying is taken by some as an abandonment of the Son by the Father.

]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]]

සමහර ලිබරල්වාදීන් ද ඇතුළත්ව Posh වාමාංශිකයන් පුරුද්දක් ලෙස ‘ආගම’ සලකන්නේ යල්පැන ගිය මුලාවක් සහ මුලා කිරීමක් ලෙසිනි. ෆොයර්බාක් තිසීස පිළිබඳ වැටහීමක් ඇති මාක්ස්වාදීන් ‘ආගම’ සලකන්නේ, විවේචනය කළ යුතු ප්රපංචයක් ලෙස මිස විචාරක අවියක් ලෙස නොවේ. ෆොයර්බාක්ට අනුව ආගම මිනිසාගේ නිෂ්පාදනයකි. මේ මිනිසා හෝ ‘නො – මිනිසා’ යනු, සමාජීය නිෂ්පාදනයකි.

සමකාලීන මිනිසාට අනුව අප මේ ජීවත්වන වෙළඳපොල ආර්ථික ක්රමය (ධනවාදය) පරිපූර්ණය. එහි අඩුවක් නැත. අඩුවක් තිබෙනවා නම් එම අඩුව ද සපුරා ගෙන මෙම ක්රමය තුළම අප ජීවත් විය යුතුය. මේ වෛරසයට පසුවත් ජීවත්වීමට ආශා කරන්නේ ධනවාදය තුළමය. එබැවින්, අපට ‘ධනවාදය’ දෙවියෙකි. ආගමකි. අප වෙනත් කිසිම ආගමක් එතරම් විශ්වාස කරන්නේ නැත. අප ‘කරන දේවල්’ නරඹන උඩ සිටිනා කෙනෙක් නැති නිසා අප කැමති දේවල් අපට කරගෙන යාමට නිදහස ඇත. ඒ නිසා, සමකාලීන යුගය තුළ ආගම අත්වාරුවක් මිස දෘෂ්ටියක් නොවේ. ආගම් මිනිසුන් අදහන්නේ විලාසිතාවකට පමණි.

ඉහත හේතුව නිසා තරුණ ජනයා ආගම් විශ්වාස කරන්නේ නැත. ආගම වෙනුවට ඔවුන්ට ඊට ආදේශ වී ඇත්තේ අන්තර්ජාලය යි. අන්තර්ජාලය ඔවුන්ගේ ආගමයි. කතිකාවත් ඇමීබාකරණය වන්නේ ඒ නිසාය.

ඒ නිසාම ‘විශ්වාස කිරීම’ සහ ‘නිර් විශ්වාසය’ යනු, තෝරා ගැනීම් අතර ඇති තවත් තෝරා ගැනීමකි. සිග්මන් ෆ්රොයිඩ්ට අනුව ආගම යනු, නියුරෝසික රෝග ලක්ෂණයකි. ලැකාන්ට අනුව ප්රතිකාරය අවසන් වන්නේ ‘දෙවියෙකු’ නොමැති ලොවක නම් මනෝවිශ්ලේෂණය සතු පාරභෞතිකය කුමක්ද?

‘ආශාව’ ඉක්මවා ‘හඹා යාම’ ප්රබල වූ ධනවාදය තුළ ආගම ඇදහීම කෙළවර වන්නේ, පරමාදර්ශ වලින් තොර අශ්ලීල විනෝදයන්ගෙනි. ඒ නිසා, ‘විශ්වාසය’ සහ ‘නිර් විශ්වාසය’ අතර වෙනස තාර්කික මනස මත ලියවෙන්නේ නැත. මන්දයත්, අප විශ්වාස කිරීම අතහැර දැමූ විගස අප වෙනුවෙන් අවිඥානය විශ්වාස කරන්නට පටන් ගන්නා නිසාය. එවිට, මිථ්යාදෘෂ්ටිකයන් බිහි වෙයි. ආගම අතහරින ජාතිවාදයා කොමියුනිස්ට්වාදය අත් හරින්නේ ද ඒ නිසාය.

බුද්ධාගමටත් ඇතුළත්ව ආගම්වලට පියවරුන් සිටිති. නමුත් අනාථභාවය පටන් ගන්නා විට ‘ආගම’ දෘෂ්ටිවාදය විචාරය කිරීමට පටන් ගනියි. යමක් ඉතා ගැඹුරින් අවිශ්වාස කිරීම නරක නැත. මන්ද දයලෙක්තිකය පටන්ගන්නේ නිශේධනයෙන්-Negation– නිසාය. පිරිමින් නිශේධ කරන දෙය ‘ආදරය’ නිසා ස්ත්රීන් විශ්වාස කරයි. ඒ ‘ආගම’ නොව පිරිමි මිනිසාවය. එමගින්, පිරිමි මිනිසා තමන් අවිශ්වාස කළ දෙය විශ්වාස කරන්නට පටන් ගනියි. ආගම දෘෂ්ටිවාදී විචාරයේ ප්රථම පියවර වන්නේ එතැනිනි.

=========================+++++++++++++++++++++++++++

ඔබට උත්තර යෝජනා නොකරන, නිවැරදි ප්රශ්නය ඇසීමට, අධ්යයනය කරන අප සමඟ එකතු වෙන්න.

ඉගෙන ගැනීමට අවශ්ය නම්, අප සමග එකතු වන්න!

ඒ සඳහා, පහත පෝරමය පුරවා එවන්න!

click..

============================]]]]]]]]]]]]

Learn…….Learn……..

Beneath the Veil: On the Truth of Islam

What is Islam – this disturbing, radical excess that represents the East to the West, and the West to the East?

Let me begin with the relationship of Islam to Judaism and Christianity, the two other religions of the book.

As the religion of genealogy, of the succession of generations, Judaism is the patriarchal religion par excellence. In Christianity, when the Son dies on the cross, the Father also dies (as Hegel maintained) – which is to say, the patriarchal order as such dies. Hence, the advent of the Holy Spirit introduces a post-paternal/familial community.

In contrast to both Judaism and Christianity, Islam excludes God from the domain of the patriarchal logic. Allah is not a father, not even a symbolic one. Rather, God is one – he is neither born nor does he give birth to creatures.

This is why there is no place for a Holy Family in Islam. This is why Islam so emphasizes the fact that Muhammad himself was an orphan. This is why, in Islam, God intervenes precisely at the moments of the suspension or failure of the paternal function (when the mother or the child are abandoned by the biological father). This is also why Islam represented such a problem for Freud: his entire theory of religion is based on the connection between God and “the father.”

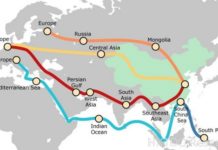

But even more importantly, it is this that inscribes politics into the very heart of Islam, since the “genealogical desert” makes it impossible to ground a community in the structures of parenthood or other blood-ties. As Fethi Benslama puts it, “the desert between God and Father is the place where the political institutes itself.”

In Islam, it is no longer possible to ground a community in the mode of Totem and Taboo, through the murder of the father and the ensuing guilt which brings brothers together – hence Islam’s unexpected actuality. This problem is at the heart of the Muslim “community of believers” – the Umma – and accounts for the overlapping of the religious and the political (the community should be grounded directly in God’s word), as well as for the fact that Islam is at its best when it grounds the formation of a community “out of nowhere,” in the genealogical desert, as a kind of egalitarian revolutionary fraternity. No wonder, then, that Islam is so appealing to young men who find themselves deprived of family and social networks.

As Moustapha Safouan has argued, it is this “orphanic” character of Islam that accounts for its lack of inherent institutionalization:

“The distinctive mark of Islam is that it is a religion which did not institutionalize itself; it did not , like Christianity, equip itself with a Church. The Islamic Church is in fact the Islamic State: it is the state which invented the so called ‘highest religious authority’ and it is the head of state who appoints the man to occupy that office; it is the state that builds the great mosques, that supervises religious education; it is the state again that creates the universities, exercises censorship in all the fields of culture, and considers itself as the guardian of morality.”

Here we can see how the best and the worst are combined in Islam. It is precisely because Islam lacks an inherent principle of institutionalization that it has proven so vulnerable to being co-opted by state power. Therein resides the choice that confronts Islam: direct “politicization” is inscribed into its very nature, and this overlapping of the religious and the political can either be achieved in the guise of the statist co-option, or in the guise of anti-statist collectives.

But let me now move to a further key distinction between Judaism (along with its Christian continuation) and Islam. As is apparent from the account of Abraham’s two sons, Judaism chooses Abraham as the symbolic father; Islam, on the contrary, opts for the lineage of Hagar, for Abraham as the biological father, thereby maintaining the distance between “the father” and God, and retaining God in the domain of the un-symbolizable.

It is nonetheless significant that both Judaism and Islam repress their founding gestures. According to Freud’s hypothesis, repression in Judaism stems from the fact that Abraham was not a Jew at all, but an Egyptian – it is thus the founding paternal figure, the one who brings revelation and establishes the covenant with God, that has to come from the outside.

In Islam, however, the repression concerns a woman – Hagar, the Egyptian slave who bore Abraham his first son. For although Abraham and Ishmael (the progenitor of all Arabs, according to the myth) are mentioned dozens of times in Qur’an, Hagar is entirely absent, erased from the official history. As such, she continues to haunt Islam, her traces surviving in rituals, like the obligation of the pilgrims to Mecca to run six times between the two hills Safa and Marwah – a kind of neurotic re-enactment of Hagar’s desperate search for water for her son in the desert.

But along with Hagar, there is in the pre-history of Islam the story of Khadija, the first wife of Muhammad himself, who enabled him to differentiate between truth and falsehood, between angelic messages and those from demons.

Muhammad was, of course, the first to doubt the divine origin of his visions, dismissing them as hallucinations, as signs of madness or as outright instances of demonic possession. His first revelation occurred during his “Ramadhaan” retreat outside Mecca, when the archangel Gabriel appeared to him, calling upon him to “Recite!” (Qara’, whence Qur’an).

Muhammad believed he was going mad, and not wishing to spend the rest of his life as Mecca’s village idiot, he decided to throw himself from a high rock. But then the vision repeated itself: he heard a voice saying: “O Muhammad! Thou art the apostle of God and I am Gabriel.” But even this voice did not reassure him; he returned to his house and, in deep despair, asked Khadija: “Wrap me in a blanket, wrap me up in a blanket.” Muhammad told her what had happened to him, and Khadija dutifully gave him comfort.

When, in the course of subsequent visions, Muhammad’s doubts persisted, Khadija asked him to tell her when his visitor returned so that they could verify whether it really was Gabriel or a demon. So, when the angel Gabriel next came to Muhammad, Khadija instructed him, “Get up and sit by my left thigh.” Muhammad did so, and she said, “Can you see him?” “Yes,” he replied. “Now turn round and sit on my right thigh.” He did so, and she said, “Can you see him?” When he said that he could, Khadija finally she asked him to move and sit in her lap. After casting aside her veil, she asked, “Can you see him?” And he replied, “No.” She then comforted him: “Rejoice and be of good heart, he is an angel and not a Satan.”

(There is a further version of this story according to which, in the final test, Khadija not only revealed herself, but made Muhammad “come inside her shift” – that is, penetrate her sexually – and thereupon Gabriel departed. She then said, “This verily is an angel and not a Satan.” The underlying assumption is that, while a lustful demon would have enjoyed the sight of copulation, an angel would politely withdraw from the scene.)

Only after Khadija provided him with this proof of the authenticity of his visions was Muhammad cured of his doubts and so could embrace his vocation as God’s prophet. The first Muslim, in other words, was Khadija, a woman. She represents what Jacques Lacan called the “big Other,” the guarantee of Truth of the subject’s enunciation, and it is only in the guise of this circular support – through someone who believes in Muhammad himself – that he can believe in his own message and thus be the messenger of Truth.

This is yet a further demonstration of my fundamental contention that belief is never direct: in order for me to believe, somebody else has to believe in me, and what I believe in is this other’s belief (in me).

This should be emphasised: a woman possesses a knowledge about the Truth which precedes even the Prophet’s knowledge. What further complicates the scenario is the precise mode of Khadija’s intervention, the way she was able to draw the line between truth and falsehood, between divine revelation and demonic possession: by putting forward (interposing) herself, her disclosed body, as the untruth embodied.

This is how Khadija’s demonstration of truth is achieved through her provocative “monstration” (disclosure), to use Fethi Benslama’s term. One thus cannot simply oppose the “good” Islam (reverence of women) and the “bad” Islam (veiled oppressed women). And the point is not simply to return to the “repressed feminist origins” of Islam, to renovate Islam in its feminist aspect: these oppressed origins are simultaneously the very origins of the oppression of women. Oppression does not just oppress the origins; oppression has to oppress its own origins.

The key element of the genealogy of Islam is this passage from the woman as the only one who can verify Truth, to the woman who by her nature lacks reason and faith, cheats and lies, provokes men, interposing herself between them and God as a disturbing presence, and who therefore has to be rendered invisible. Woman, in other words, as an ontological scandal, whose public exposure is an affront to God.

End