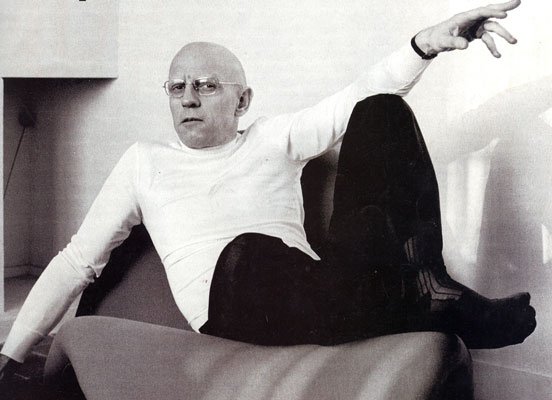

අප විසින් පවත්වනු ලබන දේශපාලන අධ්යයන පංති මාලාවේ ව්යුහවාදය [Structuralism] අධ්යයනය යටතේ බලය සහ දැනුම අතර පවතින සබඳතාවය පිලිබඳව මීචෙල් ෆුකෝ විසින් න්යාය ගත කරන ලද සංකල්ප පිලිබඳ මූලික සාකච්චාවකට ඔබට පහතින් සවන්දිය හැක.

අප සංවිධානයේ අභ්යන්තර අධ්යයන සාකාච්ඡා තුලට සීමා නොකර අප මේ අධ්යයන සාකච්ඡා සියලු දෙනා සමග බෙදාගැනීමට උත්සහ දරන්නේ සමාජය වෙනස් කිරීමට උත්සහා දරන ඔනෑම අනාගත දේශපාලන ව්යාපාරයක් විසින් මේ සංකල්ප නිවැරැදිව ග්රහණය කරගත යුතු යැයි අප විශ්වාස කරන බැවිනි.

In a Nutshell

What if we could analyze a poem the same way we can analyze a chemical compound in a test tube? You know, break it down into little bitty components, examine the parts it’s made out of, see how those parts fit together, and thereby understand how all other poems are assembled? In other words, get at the deep structure of a poem: that essential thing that makes any poem a poem, distinct from a novel, or a newspaper article, or a play, or an actual chemical compound.

This, in fact, is exactly what structuralism is about. Structuralist theorists are interested in identifying and analyzing the structures that underlie all cultural phenomena—and not just literature. They want to understand the “deep structure” of football games. Of families. Of political systems. Of fashion. Of chemistry classes and of theory study guides.

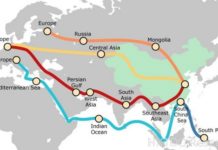

Structuralists got the notion that everything could be analyzed in terms of a deep structure from the linguist Ferdinand de Saussure. He came up with this idea that language is a “sign system” made up of unchanging patterns and rules. The structuralists who were influenced by Saussure took that deep structure idea even deeper: If underlying patterns or structures govern language (they said), doesn’t that mean that underlying patterns or structures shape all human experience?

Because structuralism emerged from linguistics, theorists from this school make a big deal about language. But what really is language, anyway? Structuralists define “language” super broadly: sure, language is that thing we do when we open our mouths and put some words together in a sentence. But for structuralists language can be any form of signaling—not just speech or words, but anything that involves communication. Red, yellow and green traffic lights? Yup, that’s a language. National flags? Check. Our fancy Louis Vuitton bag that we wouldn’t be caught dead without in public? Yes dahling, that’s key to the language of “fashion”: by sporting that bag we’re signaling to everyone who stares after us in envy: “I’m stylish and I’m loaded.”

Structuralist thought is pretty central to the way we approach reading and talking about great books. When it comes to literature, structuralist theorists care about discovering the structures or rules that govern groups of literary works. So when we talk about the narrative elements of a novel, for example—things like plot, character, conflict, setting, point of view—we’re borrowing the structuralist idea that there are certain principles or structures that can be found in all novels. The same goes for other types of literature. Whether we’re talking about epic poetry, or tragic drama, or postmodern literature, we’re assuming that there are certain “structures” that these texts have in common with one another. Like the green-means-go of traffic lights, but more relevant in a lit class.