In The Myth of Sisyphus Albert Camus seeks his own answer to the question that Kierkegaard, Dostoevsky and Nietzsche have bequeathed to us: is it possible to live without God, without any hope of salvation as death looms? At first sight the outlook is bleak: we are, says Camus, thrust into existence as into an exile with no return. From the viewpoint of eternity, we are passions that can never be satisfied, cries that go unheard. Human beings and the world do not mix. He sums up man’s tragic existence in one word: the absurd. It emerges from the fracture between the soul’s desperate desire for clarity and the incomprehensibility of reality, the gap between our craving for meaning and the cold grave that awaits us. Camus understood early on that reason – the traditional weapon of philosophy – would always be powerless to address the futile, ill-fated game of existence.

Even so, the work essentially represents a manifesto for revolt and the ecstasy of life. It is a passionate revolt that answers the question of the meaning of life: if there is any raison d’étre worthy of the name, it is born of a piece of trembling flesh. Desire, affection and generosity: these are the bread and wine of the mortal human being. Anyone who does not live to serve an immortal Creator must become a creator himself. The absurd man, as Camus calls his hero, transforms his days into a work of art, a defiant celebration of the battle which, as he knows from the outset, must eventually end in his death. Camus quotes Nietzsche: “It is not a question of eternal life but of being eternally alive.”[1] It is the destiny of the absurd man to try to make something out of the nothingness, to grasp his life from death itself. Sisyphus shows us the way: happiness is the leap we make both with and in spite of our burden.

This insight is already there in the young Camus’ poetic meditations on the “home of the soul” which saw him come into the world in 1913: Algeria. It was here, in the generous sunshine of French Algeria, that the poet’s sensibility was formed. The 20-year-old’s reflections on the home country exude a sensual amor fati, a dream that the flesh might provide an escape from exile and conquer the absurd. Here he depicts the nuptial feast between people, the earth, the sun and the sea. His hometown, Algiers, writes Camus, worships the body, warmth and an eternal present. “For those who are young and alive everything in Algiers is a refuge and a pretext for continuous triumph: the bay, the sun, the red and white terraces facing the sea, flowers and sports grounds, the cool legs of young women.”[2] The Algerians’ simple request for happiness amidst their daily misery reveals man’s innocence with regard to life and death.

Perhaps this identification with the vibrant bodies on Algeria’s beaches expresses an instinctive rebellion against the serious case of TB that had, since his adolescence, pitched the author between hope and despair. The disease threatens to deprive him forever of the Algerian sun he loves so much, and which, bedridden, he could glimpse from his window in the simple working-class suburb of Belcourt. “In this land that offers so much life, everything exudes a terror of death,” he writes from his sick bed. Anyone who understands how to live without hope in the future sees the moment as his only kingdom.

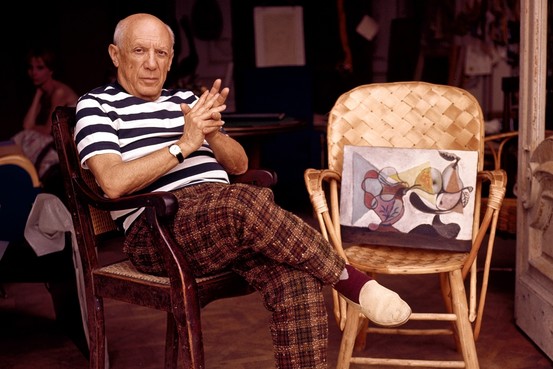

Camus survived his illness and in the early 1940s left Algiers for metropolitan France and Paris. There he published in just one year, 1942, what he called in a diary entry “The triptych of absurdity”: the essay on The Myth of Sisyphus, the play Caligula, and the novel The Stranger. This would be the start of his big breakthrough. He was soon standing shoulder to shoulder with the monstres sacrés of French existentialism, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir. He was not yet 30 years old.

One of the issues the author examines in his essay on Sisyphus – “Knowing whether or not one can live without appeal is all that interests me,”[3] – gets its acid test in The Stranger, a literary portrayal of the obsessions of the French-Algerian Meursault. We accompany him from the days surrounding his mother’s death to the day before his execution. It is Meursault himself who tells the story, oscillating between insightful indifference and moments of sensual pleasure. He knows that life itself offers no compelling reason for either the one or the other; only chance, sensuality and spontaneous impulse are able to guide a life led without any higher meaning. A man can cry or not cry at his mother’s funeral, shoot or not shoot an Arab on the beach, marry or not marry a woman who declares her love for him. When all is said and done, everything is equal and people are essentially innocent when dealing with the absurd vicissitudes of life. “As if familiar paths traced in summer skies could lead as easily to prison as to the sleep of the innocent,” says Meursault.[4] In Camus’ preface to the US edition, the young Franco-Algerian is described as a martyr for the absurd. He is a man who refuses to cheat. Neither Church, State nor morality can persuade him to give up the truths of the heart. He is at once a Raskolnikov and a Josef K, but with the important difference that he never seeks to do penance. Meursault feel no remorse, nor does he try to convince anyone that he does. He does not speak unless he has something to say. Those who keep their thoughts to themselves are not swayed by public opinion.

Ultimately, it is Meursault’s indifference that leads to his downfall. According to the prosecutor, he “[buried] his mother with a crime in his heart”, and anyone who has killed his mother – morally speaking – is cut off from human society in the same way as someone who strikes his own father down with a killer’s hand.[5] If such a callous soul goes free, then an abyss opens up that can swallow society whole. The fate of Meursault depicts the anatomy of existential alienation through the image of a lucid, absurd man who is sentenced to the guillotine “in the name of the French people” in order to protect the national community against the most dangerous crime of all: patricide.

So much, then, for the narrative’s purely existential and universal human themes. But in the margins, a different story is playing out. It makes itself heard in a number of disturbing questions: Why does Meursault fire four more shots at an already lifeless body (“flooded with joy”, as Camus puts it in an earlier draft of the novel)?[6] Why are there no Arabs present at the trial? Why are so many of them in jail and why are they all nameless? And why is a Frenchman – who has just killed an Arab in Algeria – sentenced to death by the French colonial authorities for not weeping at his mother’s funeral? What kind of social order has Meursault struck out against?

The two stories play out on two different stages and portray two distinct types of alienation. In the first one, Meursault appears as an isolated Everyman: the dismal vicissitudes of fortune lead the young stranger to act in a certain way (although it could just as easily have been another one); to kill a certain person (although it could just as easily have been another one); and to be sentenced to death by a certain fatherland (although it could just as easily have been an another one – “why not German or Chinese?” as Meursault wonders). He is the sun’s hapless puppet – it is the “murderous sun”, “the whole beach, throbbing in the sun” that drives him towards the Arab – and when the trial judge asks him to explain his motives, Meursault replies that it was “because of the sun”.[7]

The historical reality of Algeria bursts forth onto the second stage and the anonymous figure of the dead body now reveals a concrete political stranger: the Arabs of colonial Algeria. This people, reduced to a kind of natural backdrop for the European Algerians’ apparently carefree existence, show by their mere presence that something is out of joint in French Algeria. If Meursault was the absurd hero on the first stage, here he appears instead as a typical French settler whose power is underpinned by physical violence (he is a Frenchman who kills an Arab), military superiority (the revolver defeats the knife), and the discriminatory legal system (focusing on the deceased French mother rather than on the murdered Arab). Meursault’s life choices emerge, despite his indifference, as part and parcel of a specific colonial reality. He is a pied noir, a French colonist in l’Algérie Française, who says he followed his “natural feelings” on the day he killed an Arab. Where the stranger of absurd existence sees only a series of disconnected moments, with no internal connections or any deeper meaning, the political stranger uncovers an underlying solid structure, a discriminatory machinery that ultimately rests on murder.

In other words, the colonial regime’s inherent symptom (political alienation) permeates the philosophical narrative (the sense of alienation before the absurd) as its internal negating movement. Camus’ novel hints, either consciously or unconsciously, at the deep divisions that threaten to blow up l’Algérie Française from within – and force the author to consider the circumstances of his own historical and political existence. History’s dark shadow falls over the story: between European Algerians and Arabs there is no possible reconciliation, no communication, only a fight to the death. The wordless meeting not only signals that they are strangers to each other, but also that Algeria is not big enough for both of them.

When, in the posthumously published autobiographical novel, The First Man, Camus looks back on his childhood, he often returns to the atmosphere that prevailed in Algeria at the time when the novel was written. We lived, he says, cheek by jowl with this “so close and yet so foreign people”. With their “hard, impenetrable faces” and sheer numbers, the Arabs constituted “an invisible threat that we could feel in the air”.[8] The natives’ stares and muffled murmurs reminded European Algerians that they were temporary strangers in the country and that they had made themselves masters at the cost of Arab blood. It would not be long before Algeria’s population would be forced to leave the beaches only to bathe in each other’s blood.

Early May 1945 saw the first steps towards open warfare. In the midst of the French celebrations of the defeat of Nazi Germany, Algerian nationalists took the opportunity to remind them that Algeria also had the right to liberty and independence. They defied the ban on symbols of Algerian independence and refused to give way to police threats. Bloody confrontations followed: after some 100 European civilians had been found dead, the French embarked on a senseless massacre. Tens of thousands of Arabs were killed and the prisons were filled with suspected nationalists. Camus took up his pen and wrote a number of articles demanding justice for the Arab people. He argued that radical reforms were needed to reduce the disparities between European and native Algerians. No civilization could survive when “dignity” had been sidelined for a large proportion of the population. The French had to realize that the country’s Arab and Berber population were a “sister people” and that together they should lay the foundations for a “New Mediterranean Culture”. Otherwise, he warned, the whole country threatened to shatter from within; it was time for all good men of France to do their duty for the native population: “It is only through the infinite power of justice that we will be able to win back Algeria and its inhabitants.”[9]

For many Algerians, however, the massacres were a decisive turning point. Mistrust of France had grown to such a degree that that there was no turning back. Since, after over a century of French rule, Arabs were still not welcome as equal citizens, they now needed to create their own Algerian state. Inspired by the worldwide anti-colonial struggle, the Algerian Liberation Front (FLN) proclaimed a national revolution on 1 November 1954. They accused the French of betraying their own ideals: it was now the Algerian nationalists who operated in “la pure tradition de la France révolutionnaire.”[10] The Declaration of Human Rights and the right to self-determination must also apply to the Algerian people.

For eight years France would fight, to borrow a phrase from Simone de Beauvoir, “a war that dares not speak its name”.[11] The official line in France was that it was neither a revolution nor a war of independence, merely temporary disturbances instigated by fanatical terrorists. The French nation is one and indivisible, explained the regime, and is no more likely to leave Algeria than it would leave Provence or Brittany. One of the bloodiest wars of the post-war period begins and France stops at nothing to keep Algeria French: summary executions and use of prohibited weapons; systematic torture and terror against civilians; population displacement on a massive scale; and concentration camps. Nearly one million people lost their lives. During the last year of the war Algeria was a bloodbath and hundreds of thousands of Europeans were forced to flee their former homeland. A regular French civil war was soon looming large: French officers in Algeria threatened to overthrow the “traitor” De Gaulle for starting to negotiate with the Algerian nationalists. The export version of French military chauvinism fought back against the mainland government, but De Gaulle held his ground and in July 1962 Algeria won its independence.

“Right now I have I have pain in Algeria, as others have a pain in their lungs,” explains Camus shortly after the revolution broke out in 1954.[12] The increasingly savage war and the bitter debates in France forced Camus into a difficult position. He tried to develop his own stance in the ideological war that was taking shape in metropolitan France. On the one hand, he turned against the supporters of French Algeria who turned a blind eye to colonial racism and the excesses of the French army. On the other, he was unable to reconcile himself with the radical Left who embraced the Algerian nationalists unreservedly. While the French Right saw Camus as a traitor because of his criticism of French colonial policy, the Left attacked him for betraying the tradition of anti-fascist resistance. In Algeria, said Sartre, what we are seeing is the striptease of western humanism. France boasts of its universal values while it burns Muslims alive; but now the former Untermensch (“sous-hommes”) is rising up against us to assert his humanity.[13]

Perhaps the most difficult challenge for Camus came from those who saw the anti-colonial struggle as some kind of continuation of la Résistance, the French Resistance movement during the German occupation. Personally active in the Resistance, at the end of the war Camus praised those French people who, with weapons in hand, rose up against the oppressor: “A people that wants to live does not wait to be given its freedom. It takes it.”[14] The Algerian nationalists could have made these words theirs, but Camus consistently refused to equate Algerian nationalism with the patriotism of the French Resistance. For him there was no such thing as an “Algerian people”. He speaks consistently of “Arabs”, not “Algerians”. He therefore sees the nationalists’ demands for independence from France as an expression of political naivety, where they weren’t actually being manipulated by outside forces. In one of his last pieces on the war, Camus warns of the “new Arab imperialism” he feels is emerging and which he claims has its roots in Nasser and the Soviet Union. The FLN, says Camus, thus runs errands for other powers and is consequently associated with a violence that “no revolutionary movement has ever accepted”, not least the French Resistance.[15] Unlike his former friends on the radical Left, Camus has little faith in historical reason, revolutionary violence or the communist revolution: for him, not even Marx can offer people a way out of their eternal exile. In the Cold War, Camus is significantly closer to the West than the East.

Camus never breaks completely with the premise of French colonialism: that the most fervent wish of the colonized is to be recognized as equals in French civilization. The principles of the French Enlightenment – freedom, equality, fraternity – are interwoven with a colonial paternalism. Despite the torture, racism and the obvious betrayal of the native Algerians, Camus never stopped seeing France as “the best possible future for the Arab people”.[16]

At the same time, we cannot be totally sure where Camus really stood. He knew that everything he said could be used against those of his closest friends who still remained in Algeria. In the late 1950s, Camus said that he could no longer take part in the debate: “I will not, under any circumstances, allow any statement of mine to be used to give a clear conscience to a reckless fanatic who shoots into a crowd in Algiers, where my mother and all my nearest and dearest live.”[17] In January 1956, he made his last public appearance at a conference in Algiers, which, despite receiving death threats, he had helped to organize. Under the heading, “Appeal for a Civil Truce”, Camus calls for a clear declaration from all sides in the war to keep civilians out. Nothing, he says, can ever justify an innocent death.[18]

The theme of “the innocent” is already present in The Myth of Sisyphus and runs even deeper through the political philosophy that he developed under the influence of both World War II and the events in Algeria. In the novel The Plague, the play The Just Assassins, and the essay “The Rebel”, the innocent play a critical role in the distinction he establishes between revolt (which never allows civilian casualties in the struggle) and revolution (for which the end always justifies the means). The revolutionary dream of All or Nothing (absolute justice) must give way to a new social cogito as espoused by Camus in “The Rebel”: “I revolt, therefore we are”.[19] As with the people in The Plague, besieged by the arbitrary boils of death, all opposition must take its starting point in a desperate solidarity in the face of the gruesome aspects of our common destiny. We must not add to the injustices of the present in the name of justice tomorrow; that, too, bears the weight of absurdity on its shoulders.

It is in the light of these ideas that we should understand the famous yet enigmatic comment Camus made in his Nobel Prize acceptance speech in December 1957. A young militant Algerian confronted him and demanded an explanation of his stance towards the ongoing war:

I have been and remain an advocate of a fair Algeria, where both peoples can and must live in peace and equality. I have said and repeated that we must do what is right for the Algerian people and grant them a fully democratic government. […] I have always condemned terrorism. I must also condemn a terrorism that strikes blindly, in the streets of Algiers, for example, and which one day might strike my mother or my family. I believe in justice, but I will defend my mother before justice.[20]

Who then is this innocent mother – Catherine Sintes Camus? How are we to understand this mother figure that recurs throughout his writings? In a notebook from the 1930s, the 22-year-old Camus writes that, “my whole sensibility is based on my curious feelings for my mother”.[21] We have already seen that the mother figure appears in the story of Meursault, where the son’s apparent lack of concern at his mother’s death is a prelude to the moral machinery that ultimately condemns him to death. In the early autobiographical story, “Between Yes and No”, the son – disconsolate and guilt-ridden – beholds his silent mother and wonders whether he really loves her: “He feels sorry for his mother, but is it the same as loving her?”[22] In The Plague, Doctor Rieux receives a visit from his mother in Algeria and they “love one another in silence” without ever managing to “confess their affection” properly. In The Misunderstanding, however, written at the end of World War II, it is the mother who kills a man who later turns out to be her son. When Catherine Camus finally emerges in flesh and blood in his autobiography, her son is facing trial. It is she who makes him realize his limitations: “He who talks incessantly is incapable of saying in thousands of words what she can say in just one of her silences.” The memory of his early childhood and his practically deaf and dumb mother spending days on end sitting alone, quietly by herself, stuck in his memory like “glue in the soul”. She – the embodiment of innocence – fills her son with a sense of a debt unresolved.

Perhaps one might even say that the trial scene in The Stranger is a sort of literary dress rehearsal for the political predicament in which the quirks of history would place Camus: what sort of crime has the son actually committed? Is it the murder of the Arab or the betrayal of the mother? Is it justice or innocence? Even as the War of Independence was breaking out in Algeria, Camus wrote in his notebook: “Nothing in the world, even if it were innocent and just, could ever make me abandon my solidarity with my mother, who is the most important thing in the world to me.”[23]

***

Albert Camus urged his readers to look for “the dark and the instinctive” in his work, the points of concentration where literature, philosophy and life meet, the dimensions in which the universal is interwoven with both the historically specific and the individually unique. The literary characters in his writings – the mother, the Arab, justice, the sun, innocence, the absurd and revolt – reappear in new combinations throughout his life and works. During the war it was, as we have seen, the innocent mother who raised the barricade against the Arab revolution for justice. This is not the place to speculate further on the libidinal economy at work in these conceptual configurations and dislocations, but it may be worth at least asking about the place of Camus’ own father in this logic; the Lucien Camus whom he never got to meet because he sacrificed his life for the French nation in another war, World War I. It should be remembered that, indirectly, the question of the father already plays a decisive role in The Stranger – society must be safeguarded against patricide, “the most heinous of all crimes”, because it is the father who binds society together. One can wonder what it might mean for a son, in this case Camus himself, to lend his support to the Algerian nationalist attack on the very fatherland, la patrie, that his father sacrificed his life for? A father whose death also gave his surviving son the morally-privileged status of “pupille de la nation” (a war orphan, “adopted by the French nation”).

- [1] “Le Mythe de Sisyphe”, Essais, 1965, 162.

- [2] “Noces”, Essais, 68.

- [3] “Le Mythe de Sisyphe”, Essais, 143.

- [4] Camus, The Stranger, (tr. Matthew Ward), New York: Vintage International 1989, 97.

- [5] L’Étranger, Théatre, Récits, Nouvelles [TRN], Éds. Roger Quilliot et Louis Faucon, Paris: Bibliothéque Pléiade, 1962, 1194.

- [6] Ibid. 1924. “Quand j’ ai eu la main sur la gâchette, je me suis senti inondé de joie.”

- [7] Ibid. 1165ff, 1198; The Stranger, 58, 97.

- [8] Camus, Le Premier Homme, Paris: Gallimard 1994, 257. For a similar description of colonial Algeria, see Jacques Derrida, “Derrida l’ insoumis”, Le nouvel Observateur 9 September 1983.

- [9] Camus, “Crise en Algérie”, Essais, 959. See also Paul Siblot et Jean-Louis Planche, “Le 8 mai: éléments pour une analyse des positions de Camus face au nationalisme algérien”, in Camus et la politique (Éd. J Guérin), Paris, 1986.

- [10] André Mandouze, La révolution algérienne par les texts: documents du FLN, Paris: F. Maspero, 1962, 38, 45, 52.

- [11] Simone de Beauvoir et Gisèle Halimi, Djamila Boupacha, Paris: Gallimard 1962.The subject is also discussed in Serge Berstein, “Une guerre sans nom”, La France en guerre d’ Algérie, and in Le droit à l’insoumission, 29.

- [12] Camus, “Lettre á un militant algérien”, Essais, 964.

- [13] Jean-Paul Sartre, Situations V: Colonialisme et néo-colonialisme. Paris: Gallimard 1964, 85. For further reading on Sartre, see e.g., Jean-Pierre Rioux et Jean-François Sirinelli (Éds.), La guerre d’Algérie et les intellectuels français.

- [14] Camus, “Ils ne passeront pas”, Essais, 1522.

- [15] Camus, “Algérie 1958”, Essais, 1013. See also, Essais, 891.

- [16] Camus, “L’ Algérie déchirée”, Essais, 980. Cf., Joseph Jurt, “Albert Camus et l’Algérie française”, in AlgérieFranceIslam (Éd. J. Jurt), Paris: Harmattan 1997.)

- [17] Camus Essais, 1845.

- [18] “Pour une trêve civile en Algérie”, Essais, 993. See also Olivier Todd, Albert Camus, une vie, Paris: NRF 1996 cap. 43, and Herbert R Lottman, Camus: A Biography, London, 1979. 568ff.

- [19] Camus, L’ Homme Révolt (The Rebel), Essais, 432.

- [20] Camus, “Les déclarations de Stockholm”, Essais, 1881f.

- [21] Camus, Carnets I, mai 1935, Paris: Gallimard 1962.

- [22] Camus, “Entre oui et non”, Essais, 25.

- [23] Camus, Carnets III, Paris: Gallimard, 238.