හරියටම මීට වසර 10 කට පෙර තිලක් කෝදාගොඩට එරෙහිව LLPසඟරාවේ ලිපියක් ලියමින් (ඔහු ලියන්නේ කුමක්දැයි ඔහු නොදන්නා නිසා…) සුමිත් චාමින්ද විසින් ස්ලෙවොජ් ජිජැක්ට ‘යථාර්ථය’ ගැන ඇති අදහස සහ යථාර්ථය ගැන මගේ අදහස නිසි උපුටා දැක්වීමක් සහිතව පහත පරිදි පළ කළේය.

‘‘අපගේ සමාජ යථාර්ථයම රඳා පවතින්නේ සංකේතීය ප්රබන්ධයක් හෝ ෆැන්ටසියක් මගින් නම්, එවිට චිත්රපට කලාවේ අවසාන ජයග්රහණය වන්නේ ප්රබන්ධ ආඛ්යානය තුළ යථාර්ථය ප්රතිනිර්මාණය කිරීම – එනම් යථාර්ථය වෙනුවට ප්රබන්ධයක් (වරදවා) වටහා ගැනීමට අපව පෙලඹවීම නොවේ. එයට ප්රතිපක්ෂව, යථාර්ථයේම ප්රබන්ධමය පැතිමානය අපට ප්රත්යක්ෂ කිරීම, එනම් යථාර්ථය ප්රබන්ධයක් ලෙස අත්දැකීමට සැලැස්වීමයි.’’

– සැබෑ කඳුළුවලට ඇති බිය –

ඉහත උපුටා දැක්වීමෙන් නතර නොවන සුමිත් චාමින්ද තම ප්රහාරය තවදුරටත් කෝදාට එරෙහිව යොදමින් මෙසේ ප්රකාශ කරයි.

‘‘කෝදාගොඩ ඉහත මූලික සිසැකියානු ස්ථාවරයට ඉඳුරාම පරස්පර මතයක් දරමින් ‘මේ මගේ සඳයි’ ඊනියා ප්රකෘතියට වඩා සමීප වූ යථාර්ථවාදී එකක් යැයි නිගමනය කරන්නේ ‘මේ මගේ සඳයි’ පිළිබඳව විශේෂයෙන්ම දීප්ති කුමාර ගුණරත්න විසින් කරන ලද සාවද්ය විචාරය අනුගමනය කිරීමෙන් බව පෙනේ. එම විචාරයේ දී දීප්ති ගුණරත්න හඳගමගේ කෘතිය ලාංකේය ‘යථ’ (Real) සිනමාවට නඟා ඇතැයි තර්ක කළේය. මෙහි දී ඔහු යථාර්ථයට සහ යථ (Reality and Real) පිළිබඳ මූලික ලැකානියානු සංකල්ප වැරැදි ලෙස තේරුම් කරමින් ‘යථ’ යනු යථාර්ථයට වඩා ප්රාග්මය පැවැත්මක් (a Priory) ලෙස අර්ථකථනය කර ඇත. ලැකැනියානු නිර්වචනය අනුව ‘යථ’ සංකේතීය යථාර්ථයට පූර්වයෙන් පවතින හෝ ඊනියා ප්රකෘති තත්ත්වයක් නොව සංකේතකරණයෙහිම අසමත්කමයි. ඒ අරුතින් යථාර්ථයට වඩා යථ නිරූපණය කරන සිනමා කෘතියක් ලෙස ‘මේ මගේ සඳයි’ වර්ගීකරණය කිරීම න්යායිකව වැරැදිය’’

– LLPසඟරාව – 2006, පෙබරවාරි – පිටුව 59 –

ඉහත ප්රහාරය මදි නිසා සුමිත් චාමින්ද ලිපියට පළමුව ඇඳ ඇති හතරැස් කොටුවක කෝදාට මෙසේ සරදම් කරයි. ‘‘තිලක් කෝදාගොඩ මහතාට යථක් වූ මෙම ලිපිය දැන් අපි පාඨිකාවට යථාර්ථයක් කරන්නෙමු.’’ සුමිත් චාමින්ද දෙවන වරට කෝදාට ගසන මෙම පහර නිසා ජිජැක් පිළිබඳ සර්වතෝබද්ර විපරීතභාවයක පෙළෙන ඔහුගේ දැනුම පුපුරා යයි. එනම් ‘යථ’ යනු සංකේතනයේ අසමත්කමක් නොව අවශ්ය නම් සවිඥානික තලයේ දී එය සංකේතනය මඟින් වටහාගත හැකි බවයි. චාමින්ද මීට වසර 10 කට පෙර යථාර්ථය වටහා ගත්තේ ඉංග්රීසි යථානුභූතවාදයට අනුවය.

චාමින්දට අනුව ‘යථාර්ථය’ යනු මනසට පිටතින් පවතින සැබෑ දෙයයි. ජිජැක් පිළිබඳ අනෙකාගේ දැනුම හිස්ටෙරික කතිකාවෙන් ප්රශ්න කරන (ඔබ කියන ජිජැක්ගේ දැනුම නිවැරදි යැයි ‘මම’ භෞතීෂ්ම කළ යුත්තේ ඇයි? – මෙය හිස්ටෙරිකයාගේ ආත්මීය ස්ථාවරයයි – Regarding Dr. Prabha Manurathne) චාමින්ද යථාර්ථය පිළිබඳ ලැකාන්ගේ ප්රවාදය මීට වසර දහයකට පෙර වටහාගෙන තිබුණාද?

‘යථාර්ථය’ පිළිබඳ ලංකාවේ මිනිසුන්ට පුරුදු වී ඇති මතිය වන්නේ එය මනසට පිටතින් ඇති ස්ථිර දෙයක් යන්නය. නමුත් යුරෝපයේ ප්රචලිත දර්ශනයට අනුව ‘යථාර්ථය’ට පිහිටුම් තුනක් සංකේත පිළිවෙළ තුළ ස්ථානගත කළ හැකිය.

(1) සාරාර්ථක යථාර්ථය – Reality – in – itself – දැනුමක් ලෙස යථාර්ථය ආත්මීයකරණය වීම.

(2) පරාර්ථක යථාර්ථය – Reality – for – itself – දැනුම ලෙස වාස්තවිකකරණය වීම.

(3) ඕපපාතික යථාර්ථය – Reality – in – and for itself – ආත්මීය අවශ්යතාවයක් සඳහා බාහිරත්වය ග්රහණය කිරීම, අනන්ය වීම – මෙය අවිඥානික යථාර්ථයයි.

අප ඉහත දී පහදන්නේ යථාර්ථය පිළිබඳ අදහසේ ආකෘතිමය චලනය මිස සරල රේඛීය වර්ධනය නොවේ. කෙටියෙන් කිවහොත් ‘යථාර්ථය’ පිළිබඳ යුරෝපීය දර්ශනය ගැන සරල හෝ අවබෝධයක් චාමින්දට එකල තිබුණේ නම් ‘යථාර්ථය’ පිළිබඳ ස්ථිතික (Static)අදහසක් ජිජැක් සමඟ ආබද්ධ කරන්නේ නැත.

අප විසින් ඉහත විදාරණය කරන ලද්දේ ‘යථාර්ථය’ පිළිබඳ දාර්ශනික අදහසයි. අපි ඊළඟට ‘යථාර්ථය’ පිළිබඳ මනෝවිශ්ලේෂණ අදහස සලකා බලමු. ඊට අනුව යථාර්ථය තුළ ඇති යථ යන්න මිනිස් ආශාවට (Desire) තුල්යය. මෙය හේගල්ගේ දර්ශනයෙන් කොජෙව් අර්ථකථනය කළ ආත්මයයි. ලැකාන් ෆ්රොයිඩියානු අවිඥානික ආශාව දාර්ශනික සන්දර්භයක් තුළ තබා විග්රහ කිරීමට උත්සාහ කරයි. ලැකාන්ට අනුව යථාර්ථය තුළ ඇත්තේ අනුභූතියට හෝ බුද්ධියට පමණක් ඌනනය කළ හැකි ඥානයක් නොවේ. කාන්ට් නම් දාර්ශනිකයාට අනුව යථාර්ථය නම් ප්රපංචය (දෘෂ්යමානය පිළිබඳ අත්විඳීම) ඉක්මවා ගිය තත්ත්වයක් ලෙස හඳුනාගත හැකිය. එය නිශ්ප්රපංචයයි. එනම් බුද්ධියට සහ අත්දැකීමට ග්රහණය නොවුණ ස්වායක්තයන් යථාර්ථය තුළම ගිලී ඇත. ඒවා අනුභූති උත්තරය. එබැවින් යථාර්ථය යනු අස්ථියක් මෙන් ස්ථිතික දෙයක් නොව තුවාලයක් මෙන් ගතික දෙයකි. මෙම තුවාලයට පැවැත්මවල් දෙකක් ඇත.

(A) අනෙකාගේ ආශාව කුමක්දැයි මම නොදනිමි. එය කුමක්දැයි සෙවීමට මම ගවේෂණයක් කරමි. එම ක්රියාවලිය ෆැන්ටසියයි. අනෙකාගේ ආශාව මෙන්ම මේකයි යනුවෙන් මම ගොතන ආඛ්යානයට අනෙකා අත දිගුකර එකඟ වුවහොත් යථාර්ථය යනු හොඳ වූ තුවාලයකි. එය කැළලක් පමණි.

(B) මා විසින් අනෙකාගේ ආශාව මෙන්න මේකයි යනුවෙන් ගොතන ආඛ්යානය මගේ අනෙකා ප්රතික්ෂේප කළහොත් එවිට යථාර්ථය යනු තුවාලයකි. ඒ තුළ ක්ෂුද්ර ජීවින් ජීවත් වෙයි.

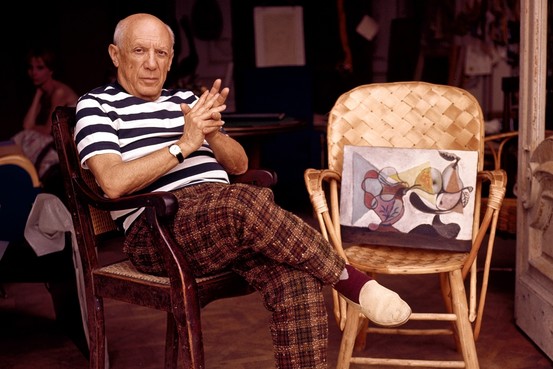

Deepthi kumara Gunarathne

සුමිත් චාමින්දට නිවැරදිව වටහාගත නොහැකිවූ සංකල්පීය පදනම ගැන අවබෝධයක් වසර 10 කට පසු පළ වූ පහත රචනාවෙන් ඔබට වටහා ගත හැකිය.

පොත් නොකියවා එපරිදිම පොත් නොකියවන පුද්ගලයකුගෙන් පොත් වල ඇති දේ ගැන අසාගෙන ඒවා ගැන නන් දොඩවන කෝදාගොඩ සහෝදරයා කවදා මොක්පුරය දකීද ??

Does this modify the view of the Lacanian Real as a transcen dental impossibility?

The notion of the Real presupposed here is the Real-as impossible in the sense of the big absence: you always miss it, it’s a basic void and the illusion is that you can get it. The logic is that whenever we think we get the Real, it’s an illu sion, because the Real is actually too traumatic to encounter: directly confronting the Real would be an impossible, inces - tuous, self-destructive experience. I think that I am partially co-responsible for this serious revisionism, to put it in Stalinist terms. [Not Deepthi ]I am co-responsible for the predominance of the notion of the Real as the impossible Thing: something that we cannot directly confront.[To whom it may concern] I think that not only is this theoretically wrong, but it has also had catastrophic political consequences insofar as it opened up the way towards thiscombination of Lacan with a certain Derridean-Levinasian problematic: Real, divinity, impossibility, Otherness. The idea is that the Real is this traumatic Other to which you cannot ever answer properly. But I am more and more convinced that this is not the true focus of the Lacanian Real. Where then is the focus?

With the logic of Real-as-impossible you have this notion of the unattainable object – the logic of desire, where desire is structured around a primordial void. I would argue that the notion of drive that is present here cannot be read in these transcendentalist terms: that is to say, in terms of an a priori loss where empirical objects never coincide with das Ding, the Thing.

The result of all this is that, for Lacan, the Real is not impossible in the sense that it can never happen – a trau-matic kernel which forever eludes our grasp. No, the problem with the Real is that it happens and that’s the trauma. The point is not that the Real is impossible but rather that the impossible is Real. A trauma, or an act, is simply the point when the Real happens, and this is difficult to accept. Lacan is not a poet telling us how we always fail the Real – it’s always the opposite with the late Lacan. The point is that you can encounter the Real, and that is what is so difficult to accept.

What consequences does this perspective hold for the theory of ideology? Does it mark a departure from the psychoanalytic view of ideology that offers a construction of reality as a way of escaping the horrifying condition of the Real?

I am no longer satisfied with my own old definition of ideology where the point was that ideology is the illusion which fills in the gap of impossibility and inherent impossibility is transposed into an external obstacle, and that therefore what needs to be done is to reassert the original impossibility. This is the ultimate result of a certain transcendentalist logic: you have an a priori void, an original impossibility, and the cheat ing of ideology is to translate this inherent impossibility into an external obstacle; the illusion is that by overcoming this obstacle you get the Real Thing. I am almost tempted to say that the ultimate ideological operation is the opposite one: that is, the very elevation of something into impossibility as a means of postponing or avoiding encountering it.

Again, I am almost tempted to turn the standard formula around. Yes, on the one hand, ideology involves translating impossibility into a particular historical blockage, thereby sustaining the dream of ultimate fulfilment – a consummate encounter with the Thing. On the other hand – and this is something you have already touched upon in your excellent ‘Ideology and its Paradoxes’ paper – ideology also functions as a way of regulating a certain distance with such an encounter. It sustains at the level of fantasy precisely what it seeks to avoid at the level of actuality: it endeavours to convince us that the Thing cannot ever be encountered, that the Real forever eludes our grasp. So ideology appears to involve both sustenance and avoidance in regard to encountering the Thing.

ඔබේ අදහස කියන්න...