I wonder if Ariyaratna Athugala’s novel “Saho” is about contemporary man and not about society. But for many critics, it’s a great novel about the university community. There is no doubt that it is a unique novel written recently. But that is not because it makes an assessment about a certain section of society.

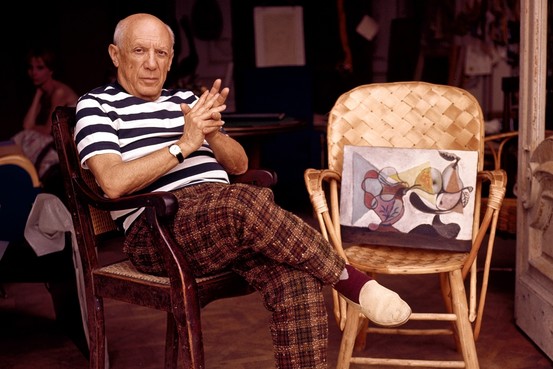

One of the common misconceptions among contemporary literary critics is that the novel should delineate society. Nevertheless, considering all the novels that have been published in the world, I suggest that no such thing is revealed. As Milan Kundera states in his book.

The Art of the Novel that “All novels, of every age, are concerned with the enigma of the self. As soon as you create an imaginary being, a character, you are automatically confronted by the question: What is the self? How can the self be grasped? It is one of those fundamental questions on which the novel, as novel, is based.”

If someone says that a novel should be considered a social analysis, I suggest reading a more appropriate sociological book. This does not imply that society should be excluded in every respect from the novel. The social context in which the novel unfolds cannot be ignored. However, if I elaborate the view of Kundera on this issue, a novel examines not social reality but human existence. And the society that the novelist reads is not the society that the sociologist reads. History is not the history that the historian reads. It is a history or a society that can only be expressed by a novel.

Enigma of the self

Another important point Kundera emphasises is that even the first European storytellers, unaware of the psychological dimension of the novel, were intrigued by the enigma of the self. Boccaccio simply described the action and the adventurous experience. What we need to understand from these hilarious stories is that the main factor that distinguishes man from each other is his actions. It is through these actions that one separates oneself from others and becomes an individual. Kundera quotes Dante.

“In any act, the primary intention of him who acts is to reveal his own image.”

Now, the question we confront at this juncture is what a novel is. Or rather state of the Sinhala novel. Let me describe my own experience of Sinhala novels here. In 2014, as a member of the Swarna Pusthaka Literary Awards Jury, I read about 130 novels published that year. What I found there was that about 75 percent of those novels were about ambition. Ambition is a drive or rather eagerness to rise to the top of society.

Even Liyanagee Amarakeerthi’s Kurulu Hadawatha, which was selected as the best novel of the year, is one such novel. However, such novels are popular among readers. This is because it allows the reader to meet her own desire. Accordingly, the nature of the novels currently being written is either a self-expression of ambition or it is lost in vicious commentary on enigma of feminine sexuality.

Content

This dialogue about Ariyaratne Athugala’s novel takes place at a time when the Sinhala novel is facing such a destiny. One of my points of interest here is the question of what the form of the novel should be. Many people consider content to be the most important aspect in a novel. What they disregard is that the form is the content itself. Even Sigmund Freud interprets a dream by the way it was seen, not by its content. (Read Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams) It means the form not the content.

Even the post-Marxist critic Friedrich Jameson suggests that this method could be developed into literary review. It is within this form that political significance of the novel is defined. In that sense, Saho as a novel is important to us because of its uniqueness of the form.

We have seen three significant works of art, namely, Handagama’s Death in an Antique Shop, Eric’s Petha and Athugala’s Saho in recent days. All three works have a similar forms. Exceptional characteristics of this novel Saho is its naming of the characters. They are Sandhu, Rathu, Tharu, and Hiru. But the character we always miss is Rathu. When it comes to Rathu and Tharu, our eyes are deceived and we read Rathu as Tharu. This tangle urges us to read the novel cautiously. The mystification over these names reminds me of Franz Kafka. The protagonists of two of his novels were named as K. It’s not just a name, it’s just a letter

Saho

The other characteristic of this novel is that same thing happening again and again as the form of the novel. This repetition was also seen in the works of art I mentioned above. The central theme of this novel is Saho’s death.

Who killed Saho? Did he die from being stoned by Tharu during the protest? Did Saho express his love to Sandu before he went to the protest, but she refused and he killed himself? Eeveryone revolves around this particular fact of Sasho’s death.

This can be compared to the endeavor of Sisyphus in the myth of Sisyphus. Sisyphus pushes a large rock to the top of a mountain with great effort. But as soon as he reaches the top of the mountain, the rock overturns and falls back to where it was before. Sisyphus pushes the stone back as before. The crux of the myth is that the same thing happens again and again and this repetition applies even to our lives.

This repetition is the form of the novel we discuss here. Things related to Saho’s death are called signifiers. Even Saho”s death is a signifier. The master signifier which controls all the characters in the novel is Saho’s death. One of the characters in the novel, Tharu, tries to have a romantic relationship with Sandu. The question is why she constantly refuses his request. All these situations revolve around Saho’s death.

Eventually, Sandu digs into Saho’s grave and finds a bullet in his skull. It reveals that Saho was killed in a police shooting. The novel ends with Tharu and Sandu having a sexual encounter. Everyone else is dancing around them. With that revelation, the thought of being responsible for Saho’s death is removed from everyone.

Saho is an empty signifier. It makes no sense. It is powerful because it lacks that meaning. An empty signifier cannot be easily destroyed. If he was shot dead by the police, he would be a worthy person. Sandu finds a bullet in his skull. Then he will no longer be an empty signifier. As a result, Sahoo and Sandu are no longer barred from having sex

This is by no means a serious critique of the novel. It is true that such a thing cannot be accomplished in such a small column. My purpose here was to point out that there should be a new discourse on the direction of the novel. I have discussed Athugala’s novel here as an access to it.