Philosopher and activist Srećko Horvat thinks #deleteFacebook isn’t enough to stop big companies from getting rich by harvesting our personal data, and influencing elections in the process. At the same time, he recognises that the internet might be the best tool we have to connect and create a truly global community. ‘What we need is a radically new system, an “Internet of the People”.’

On a cold February morning in 2008, hundreds of people turned up outside the Church of Scientology building in New York. They carried placards and every single one of them wore a threatening mask – most noticeably the Guy Fawkes mask from the V for Vendetta movie. They were members of the messaging board 4chan, ostentatiously there to protest Scientology. But mostly, they just wanted to see what would happen. Could a community that so far had only existed on the internet go mainstream and make an impact in the real world?

Turns out, it could. For the last ten years, organizing any kind of protest without the internet and social media has been unthinkable. The Guy Fawkes mask reappeared at sit-ins organized by the Occupy movement and became the symbol of Anonymous, the hackers collective. In 2011, Facebook and YouTube fanned the flames under the uprisings in the Arab world. In 2016, #Ferguson became Twitter’s most used hashtag representing a social cause ever at 22,7 million mentions – followed on the heels by #BlackLivesMatter. Demonstrations against gun violence in America were organized all around the world in 2018 using #NeverAgain and #Marchforourlives.

“The electorate is not only manipulated and influenced by social media, we’re also approaching dystopian times in which democracy itself can be ‘preprogrammed’”

At the same time, the relationship between social media and activism is an uncomfortable one. Much has been written about ‘slacktivism’ or hashtag activism; people supporting a cause by liking something on Facebook or signing an online petition but not actually taking action. Another potential problem is the difference in values between the corporations behind social media, and the protest movements themselves. Can you still believably use Facebook to reach people when you’re protesting against the excesses of capitalism, or in defense of online privacy? Even when you know the social network has leaked personal data from 87 million users to political advertising company Cambridge Analytica, which used the data to campaign for Brexit and Donald Trump?

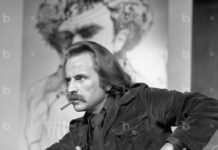

We asked philosopher and left-wing activist Srecko Horvat (Croatia, 1983) what he makes of this dilemma – and how he sees the future of social media protesting unfolding. Horvat has been writing for years about the demonstrations that have made international headlines, like Occupy and the protests at the G20 in Hamburg. He is also deeply interested in technology: Tinder helped inspire his philosophical book The Radicality of Love, and he has often spoken in defense of Julian Assange. Horvat is critical of capitalism and an advocate of direct democracy. Currently he is on the road campaigning for the Democracy in Europe Movement (DiEM25), the platform he co-founded alongside Yanis Varoufakis.

Were you concerned about the recent revelations concerning Facebook? Did you delete your account?

‘Luckily I’ve never had a Facebook account, so I’m not in the traumatic position of the millions who feel addicted to Facebook (see: “I’m angry at Facebook- but I’m also addicted. How do I break free?”) Such a column is reality now, not a line from a science-fiction movie like “The Circle”.

‘I am concerned but not at all surprised by the recent Facebook and Cambridge Analytica revelations, everything was pointing in that direction for years already. To put it in old Marxist terms: when you have a capitalist monopoly (Silicon Valley) that owns the means of mental production, then it is just a matter of time until this technological beast starts influencing, or even pre-determining elections. It was pathetic to see Mark Zuckerberg in front of Congress blaming the “Russians” for election interference, instead of admitting that data harvesting and user-influencing are at the core of Facebook’s business model.’

Why do you think Facebook’s impact on society is negative?

‘Facebook is addictive. An early investor in Facebook, Roger McNamme, said that Facebook has “altered” people’s brains (“Those people have all been Zucked”) and Sean Parker [first president of Facebook] added that, “God only knows what Facebook is doing to our children’s brains”. What is the consequence of that? It is time to re-think what democracy really means in the early 21st century. The electorate is not only being increasingly manipulated and influenced by social media, but we are approaching dystopian times in which democracy itself can be “preprogrammed”. To put it in other words: how much free will do you really have if your actions [including your vote] are already predicted and programmed by the Algorithm?’

But back in 2011 Facebook got a lot of credit for its role in the Arab Spring uprisings. Have we become too cynical or disillusioned about the internet’s revolutionary potential?

‘Yes, during the so-called “Arab Spring”, technology had a decisive role. But let us not forget that during the height of the Egyptian uprising and occupation of Tahrir square, the Mubarak government, in partnership with Vodafone, cut off telecommunications, depriving demonstrators from using their mobile phones and Twitter services. More recently, the UN’s fact-finding mission in Myanmar declared that social media had “substantively contributed to the level of acrimony, dissention, and conflict” in that country. So you can see that “social media” can both be used for emancipation and for conflict.

“If we don’t build alternative and decentralized modes of communication we are doomed to fail”

‘There is a long tradition in philosophy, from Plato to Derrida, and most recently Bernard Stiegler that understands technology as “pharmakon”, an ancient Greek term which designates both a remedy and a poison. The point is not to fall into the trap of viewing it as either/or; technology is both a remedy and poison, at the same time.

‘For example: Albert Einstein is not responsible for the atom bomb, and Nikola Tesla would in no way be happy with Elon Musk’s “Tesla”. Because in Tesla’s mind, knowledge (and energy) was supposed to be free and available to everyone. Today we are in dark times, in which not only are knowledge and energy privatised, but our very desires can be manipulated. We can use social media and subvert it as much as we want, but if we are not at the same time, building alternative and decentralized modes of communication, we are doomed to fail. There is no point in dreaming about an “escape” to a world without technology. The only answer can come from changing it from within, we have to reprogram the Algorithm.’

Some people have argued that if we delete our social media accounts for privacy reasons we are robbing ourselves of the best tool we have to organize protests and petitions and make smaller movements visible for free. What would you say to them?

‘I believe in “subversion” – use all means possible as long as you are not co-opted by the system!’

At the Brainwash festival in Amsterdam last year, you said the only way to save the world is by building something that is worth losing – a truly global community. Is it possible to achieve the dream of building a global community without companies like Facebook? After all, ‘building the global community’ is literally what they say their mission is.

‘To answer your question, I would pose the question without a negation: is it possible to achieve the goal of building a global community with companies such as Facebook? After the Facebook revelations, I hope even a fool knows that it is precisely with companies like Facebook that it is difficult not only to build, but to imagine a different world. If you want a world in which narcissism and fake friendships reign, choose Facebook.

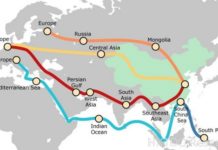

‘If you want a world in which technology serves to develop and emancipate the true potential of humans, which wouldn’t be based on the commodification of all the aspects of social and emotional life, what do you do? Here’s the problem. It’s not sufficient to “delete Facebook” if there is no other global alternative. Facebook was too easy, you just join and become part of the narcissistic Algorithm. Creating something new is much more difficult. There have been many positive examples such as the blockchain or FairCoin – decentralized systems that are not based on manipulation or exploitation. But without this struggle taking place on an international level, it is very difficult to imagine a future without Facebook – and what it represents.’

If Big Tech is here to stay, how should we deal with it? Is it a problem for your ambitions with DiEM25?

‘It is a major challenge, not only for DiEM25, but for all of us. I don’t believe preemptively that any struggle is destined to fail. But if we are not quick and successful, the question will be whether it will still be possible to lead any struggles against the final privatisation of the General Intellect. What will happen if even resistance becomes preprogrammed?

‘What we need today in Europe is a comprehensive and effective pan-European response to Big Tech. I am not talking about Macron’s plans or the recent EU artificial intelligence pact. My fear is that both Macron’s plan and the EU/AI pact will use lots of public funding in order to foster an even bigger privatisation which is yet to occur. To put it differently, what we need is an “Internet of the people”. We need a radically new system that wouldn’t be based on commodification of transport and sleeping (like Uber or Airbnb), and that wouldn’t allow big Silicon Valley companies to progressively privatise not only our (“smart”) cities, but our imagination.’

Has social media made this generation lazy when it comes to protesting against perceived injustice?

‘I would say here you have something that the Austrian theorist of psychoanalysis Robert Pfaller called “inter-passivity”. It is a state of passivity in the presence of the potential of interactivity. Pfaller started from questions such as, ‘why do people record TV programmes instead of watching them?’ Today, twenty years after Pfaller for the first time developed this theory, we should apply it to “social networks”. How many times did it already happen that an “event” on Facebook was created to “protest” something and thousands of people joined and shared, but in the end the central square of a city was half-empty? This is “inter-passivity”, when social media- its very mode of presence and perpetual clicking – becomes a surrogate for real action. At the same time, it is precisely technology which can enable emancipation. And again, we are back to the pharmakon.’

On Twitter you called the current Facebook scandal a ‘small footnote’ to a ‘deeper AI-driven transformation of politics’. What do you think AI will mean for the future of politics?

‘It is already the case in the financial world that multi-million dollar trades and transactions are being made by machines. And not only that. It is becoming normal that these transactions are not being made between humans and machines, but between intelligent machines themselves. Speed is politics. The ability to predict becomes a sort of self-fulfilling prophecy, just like in [the Spielberg movie] Minority Report: except that you don’t have the prevention of crimes from the future anymore, but you have politics that are increasingly based on this sort of new temporal structure. If the algorithm already knows before an election who we are going to vote for based on what we “like”, why should we still go to vote?’

You might say the algorithm is already deciding for us. Didn’t we see it with Trump’s victory and Brexit?

‘Yes, but if we don’t get our act together, in a near future this will be remembered as the early days of a much more radical transformation of what we understand under “politics”.’

What advice would you give to young Europeans today?

‘The change can come only from the future. The future is now.’