Wang Hui and En Liang Khong

13. January 2014

The luminary of China’s emergent “New Left” speaks about the lessons of labour unrest, the Cultural Revolution as taboo, and post-party politics.

As a leftist and writer living in Beijing for the past four months, the ways in which the capital is haunted by its Maoist ghosts have fascinated me. From Cultural Revolution-themed restaurants to evenings of revolutionary opera, the memory of the Revolution is relegated to a highly commodified pop culture and depoliticized nostalgia.

And every morning as I cycled through Peking University teeming with students, I would pass the campus ‘triangle’ where demonstrators once massed during the heady 1989 protests. As that generation navigated the reform era, I wondered, what legacies did they cling on to?

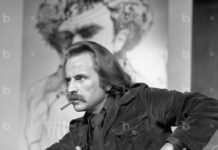

Wang Hui was there in 1989. Writing bitterly years later, he remembered, “as I departed from Tiananmen Square in the company of the last group of my classmates, I felt nothing but anger and despair.” But banished to a re-education camp in Shaanxi province, Wang made some revelatory discoveries as he opened his eyes to the injustices rural China was being subjected to: “I suddenly realized how far my life in Beijing was from this other world.” Wang’s voice has emerged as one of those of a number of Chinese critical thinkers capable of ripping through the nation’s collective cultural amnesia, in its devastating attack on the social and ecological costs of the Chinese miracle. This strain of leftwing thought is a vital counter to those of China’s liberal enlightenment who advocate neoliberal reform. Talking to Wang, now a specialist in Chinese intellectual history at Beijing’s Tsinghua University, I began to sense how the revolutionary legacy is in fact inseparable from the intellectual life and labour disputes that are shaping modern China.

China in revolt?

Refusing to seek salvation in the dichotomy of state and market, Wang’s critical thought is grounded in a deep sympathy for the potential of labour movements. A valuable tributary to this was Wang Hui’s own fight several years ago against the illegal privatisation of a textile factory in his home town of Yangzhou, in which he helped workers bring a lawsuit case against the local government.

Wang’s “small story”, he tells me over tea in his university offices, is one way of getting inside the larger “macro-landscape of China, from the late 1990s to the early years of this century, in which the privatisation of state-owned companies and industries has left huge numbers of workers unemployed, without proper compensation.” China’s capitalist turn, begun in the late 1970s under the leadership of Deng Xiaoping, has constituted a privatisation project through which state and party officials have enriched themselves.

The “institutional basis for corruption”, Wang argues, flows directly out of this private ownership of state-owned enterprises. “Corruption is not only about the corruption of individuals,” he reminds me, “but also the process of privatisation through which many who are in power, together with investors, can shift money from public property into private pockets, and get rid of the state’s responsibility for the working class.” These days distinguishing between public and private in China has little meaning. In both, bureaucracy rules, according to a shared logic of political pacification, economic growth and the narrow interests of a propertied class. During the 1990s there was a liberal hope that China’s new entrepeneurs would create a democratic vanguard. But they forgot that the new business elite was fully dependent on the one-party state and above all its exploitation of labour.

Wang has consistently centred his concepts of social justice in the importance of social movements. One of his greatest intellectual insights was to show how western neoliberal visions of the 1989 Tiananmen protests, seen as purely a student movement for democratic rights, had failed to appreciate how other parts of society shaped their defiantly socio-economic tone, massing in revolt against privatisation and in anticipation of future movements against neoliberal globalisation. Tiananmen’s latter stage had been strengthened by the deeply socialist underpinnings of significant worker participation, rising in support of the students, and it was this prospect of a mass withdrawal of labour that so frightened Party elites into the massacre of 4 June 1989.

But if the scale of worker involvement imbued 1989 with remarkable potential, what of the volatile labour unrest that continually erupts today? The Chinese working class is fighting, Eli Friedman writes in a recent essay for the radical journal Jacobin, in “undeniably the epicenter of global labor unrest.” But reflection on such resistance leaves Wang Hui far from sanguine: “China may have the biggest working class in the world, but it is a different story when you talk of its politics. Of course every day you see different protests, but what of its class consciousness? Predominantly we see disputes focused around raising incomes or certain guarantees of social security. This is a legal struggle focused on individual rights rather than the working class.”

“But we also have strikes, such as in the Honda factory a few years ago,” Wang concedes. “Such strikes resume the collective struggle, either against the boss or local governments for unfair treatment of workers, or, as in the Honda strike, workers can try to establish a new union by themselves. This is a more classical form of the working class movement, in its organisation, but there are few cases of it.” The relocation of industrial capital from the coast to the interior is a new development that has also influenced labour struggles. “When global capital like Foxconn moved inland, especially after the 2008 financial crisis, they suddenly faced the reality of a labour shortage. This forced factories into improving working conditions,” Wang explains. “Still,” he adds, “this is far from a fully formed class consciousness.”

Over 400 million workers in state-owned enterprises were sacked in the mid-1990s, to be substituted by a new working class of rural migrant workers. Meanwhile the ‘hukou’ system of household registration keeps such workers in a violent state of apartheid, formalising the denial of peasants’ education and welfare rights, upholding low wages, and refusing them roots in the city. This spatial separation means migrants’ struggles remain spontaneous, isolated, and show similarly little sign of class consciousness.

The absence of a growing consciousness in the numerical expansion of the working class might seem like a contradiction. But it has been conveniently enforced by privatisation, which suppressed working class politics by dealing a fatal wound to state sector workers. Morale among those who persist in the state sector is low, while rural migrant workers have little expectation of any rights. And the indelible memory of Tiananmen has informed the repressive government model for dealing with labour resistance. In 2002 during the Daqing Oilfield workers’ protest, tanks were sent in to circle the city. “In twentieth century China, the working class was small compared to the population – only a couple of million by 1949. Now we have hundreds of millions of workers. In the Cultural Revolution you saw various forms of active class politics. But now with the biggest working class, there is no comparable class politics,” Wang says, adding, “which is when I begin to talk of a crisis of depoliticization.”

The spectre of Mao

The Chinese movement termed the ‘New Left’ is fundamentally different from the 1960s new left of the west. The former is used to designate an emergent interrogation of globalization and privatization on the Chinese left different from the challenge of the old Stalinists, and actually originated as a mud-slinging label applied to certain intellectuals accused of wanting to return to the Cultural Revolution.

But setting such slander aside, there is no doubt that there are those in the Chinese New Left who believe the revolutionary tradition in China is far from exhausted. “I grew up during the Cultural Revolution as a student in primary and middle school. Our generation therefore was quite familiar with workers, peasants and industrial technology. Every semester we went to the factories and the countryside to work with peasants and workers. Back then students had a broader social experience,” Wang remembers. “For our generation, this was our experience, and I do believe there were positive elements there.”

Wang warns against the perils of making easy simplifications reducing the Cultural Revolution to mob rule. Such analyses so often find themselves aligned with a liberal dislike of workers’ struggles, fearing that such labour movements will go beyond civil rights and call for redistribution of power and wealth. “Is the Cultural Revolution a historical period, or a campaign, or a movement for different factors? We need to ask what we mean when we talk of the Cultural Revolution,” Wang asserts. “If you define it as a monolithic period, then you blame it because of the tragedies that happened, without an analysis of the responsibility for such tragedies, their historic causes, and whether there are more radical, progressive values also to be found in these events. Talking about good and bad is not historical analysis.”

“Nobody can defend the Cultural Revolution as a whole, and also you cannot simply say that any period in history was just completely wrong,” Wang continues. “We talk about the Cultural Revolution mainly from the point of view of elites. But very few talk about it from the perspective of workers, peasants, and their different generations.” One controversial element in Wang’s thought is his focus on drawing out a socialist tradition that, he argues in The End of the Revolution, “has functioned to a certain extent as an internal restraint on state reforms” and still gives, “workers, peasants and other social collectivities some legitimate means to contest or negotiate the state’s corrupt or inegalitarian marketization procedures.” This discourse of a ‘living’ socialist tradition within the one-party state, common among leftists and nationalists, risks straying into an endorsement of the repressive Party system. But it becomes clear that Wang’s thought steers its course far away from such gullibility.

“The Communist Party depends on the revolutionary legacy for its legitimacy. This allows the possibility for people from within and outside the Party to use this legacy to negotiate policy. When you look at working class movements, in organisations and strikes, they readily draw on this tradition and its slogans. And because such slogans are legal, the government is in difficulty,” Wang explains. “Ironically, in our constitution, China is a socialist state led by the working class. If you use such a slogan, the government must face this challenge. If they negate this legacy, without negotiation or compromise, they lose legitimacy.”

For oppressed social groups, then, the revolutionary legacy is a vital historical resource that informs the struggles of working class’ rhetoric, as it formulates its protests against injustice according to the imaginary of earlier ideals. This is what the sociologist Ching Kwan Lee means by the ‘spectre of Mao’ haunting China’s class struggles.

Hence the relevance of the spat around Wang Hui’s 2012 essay in the London Review of Books: “The Rumour Machine”, examined the fall of the former party chief Bo Xilai, in a spectacular series of murderous revelations and corruption intrigue. Bo’s pursuit of a set of socio-economic policies in his municipality of Chongqing which redirected state resources towards addressing investment in social programmes, had been dressed up in neo-Maoist rhetoric. Wang’s commentary provoked a scornful riposte from the journalist Jonathan Fenby on what he considered, “Wang Hui’s predictable take on the fall of Bo Xilai – it’s all a neoliberal plot”. Indeed, “what Wang dismisses as neoliberal reforms,” Fenby insisted, “are just the changes China needs if it is to progress.”

Wang tells me that Fenby is guilty of a fatal misreading. “My argument was not over whether or not Bo Xilai was corrupt. Instead I examined how the former premier Wen Jiabao blamed Bo Xilai and the Chongqing Experiment for its return to the Cultural Revolution. To this day, the Cultural Revolution is a taboo in China, which people cannot study. But it turns out that you can use this taboo to attack people. If you link somebody to the Cultural Revolution you can delegitimise him,” Wang laments. “It is such a difficult issue, and Wen Jiabao deployed it so cheaply. Chongqing may not have been that radical, since it was still a market economy, but its possible political alternatives worried interest groups within the Party”.

Such a manipulation of history, Wang warns, is deeply unhealthy. “This makes for a very dangerous situation. On the one hand the Cultural Revolution is still very much taboo, but on the other hand, precisely because it is a taboo, you can use it against anybody you may dislike.”

Post-party politics

Jonathan Fenby’s foray onto the letter’s page repeats a criticism commonly lodged against China’s New Left, that obsessed with the one-party state, many of their arguments are drenched in a strong statist flavour. When I suggest this to Wang Hui, he replies with a rejection of the idea that liberal democracy and parliamentary elections are sufficient to fight against the monopoly of power by any state bureaucracy. “Firstly we need to understand what we mean by parties. Talking about one party or multiple party systems is not the real crisis at hand, when we talk of China. You can, like in Russia, create lots of political parties, monopolised by the powerful and the wealthy. In Iran, the levels of mobilization in elections are higher than in any European country, but people still call it a religious authoritarian regime. I recently returned from India, where there is deep disappointment with party politics. There you have very strong social movements, but with very little voice in Parliament. And it is easy to see how, if you announced that China would have a multi-party system with elections tomorrow, Parliament would immediately be taken over by China’s big capitalists. In the multiparty system, all illegal poverty, now through ‘democratisation’, will be made legal.”

Wang extends this vision into what he sees as the universal decline of the political party, whereby both China and the west’s parliamentary democracies exist in a deep state of depoliticization. In the latter, amidst macroeconomic consensus, parliament is merely a tool for enforcing stability: “There has been a tendency in the last few decades, of political parties becoming state parties. Here, the Chinese Communist Party is no longer the Communist Party in its twentieth century sense. It is a state party. It is almost completely integrated into the framework of the state, and functions as such, rather than as a political organization. And this has occurred across the world. What we witness is the political system detaching itself from the social form.”

Wang does not relinquish his democratic aspirations. “We need to think of a different kind of politics. Democracy is a very positive value, but it is for everybody. In this sense, I do not align myself with liberal democrats, nor traditional socialism. Many might believe that the Communist Party still recognises socialism as positive, and that we can convert the Party back to its earlier tradition. This is impossible, because there are so many different interest groups within the Party.” In Wang’s vision of Chinese constitutional reform, “when the Party is no longer their representative, we need autonomous organisations of workers and peasants and other social organisations to express their voice in policy-making in the public sphere, and we need all policy to be passed not only by the Party but also by Congress.” Subjecting the bureaucracy to democratic checks and opening space for democratic debate is, of course, pure anathema to the Party, which is otherwise content to deliver economic compromises from time to time, under threat of protest.

Wang Hui’s intellectual vision, led by a deep commitment to labour movements, is an important guiding force for China’s nascent new leftists. “Socialism’s legacy in China was a failed effort to find a logic for the socialist state to overcome its contradictions. That’s why the Cultural Revolution happened, in the search for a flexible division of labour,” Wang says. “For the leftwing, we need to seriously recognise and reflect on the failure to overcome inherited legacies of hierarchy and bureaucracy. But if we say all socialism’s twentieth century experiments were ‘wrong’, or that historic socialism is not actually socialism, we are simply giving up,” Wang tells me. “There is a certain political correctness among the left that implies that talking about this history links you to its disasters. This is a cheap way of doing history.”

In his slow burning 2006 film Summer Palace, the “Sixth Generation” Chinese director Lou Ye delves into the memories, trauma and disillusionment of the Tiananmen generation. In a harrowing scene, many years after the crackdown, the Chinese student Li Ti walks through Berlin, and encounters a leftwing march accompanied by the banner of Mao. Her subsequent violent suicide perfectly captures how that generation’s search for a truthful reconciliation with the failures of the Maoist era has long been fraught with danger. From the left to the right, from China to the west, reflections on the Maoist legacy are riddled with too many half-truths, dogged by euphoria or monsterisation, so preventing the emergence of a truly radical politics. “Mao has a huge, emotional legacy. He excites and irritates. People appropriate him for different purposes. Nationalists use him, and this often worries the Party. On the one hand, he is an unavoidable figure for the Party, since they cannot simply negate him, but on the other, they try to treat him in the abstract,” Wang muses. “But his legacy is still alive, both within and outside the Party. And it is alive in increasingly chaotic ways.”

very good timely article. Thanks for posting.

Comments are closed.